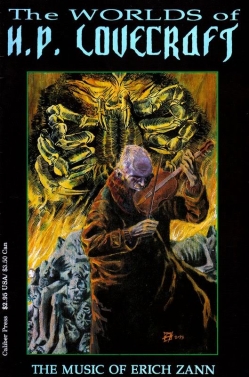

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Music of Erich Zann,” written in December 1921 and first published in the March 1922 issue of National Amateur. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

The narrator has never again been able to find the Rue d’Auseil—indeed, has never found anyone who’s even heard of it. But when he was a student, young and poor and sickly, he rented a room there. It ought not be so difficult to find it, for it had some very singular characteristics.![]()

The street is very narrow and steep—in parts, it actually becomes a staircase—and paved variously with stone slabs, cobblestones, and bare earth. Houses lean in, sometimes almost making an arch over the street. At the very end is a tall, ivy-covered wall.

The narrator, in his youth, takes a room in the third house from the top of the street, on the 5th floor. He hears music from the garret above: a viol playing wild, strange harmonies unlike anything he’s heard before. His landlord tells him that Erich Zann, a mute German musician, rents the top floor.

He encounters Zann on the staircase and begs to listen to his music. Zann’s rooms are barren, with a single curtained window. He plays, but none of the wild harmonies heard from below. All the while he glances at the window with apparent fear.

The narrator attempts to look out the window—the only one on the Rue d’Auseil high enough to have a view over the wall of the fabulously lit city beyond. But Zann, frightened and angry, pulls him back, and motions him to sit as he writes. His note apologizes for his nerves, but begs the narrator to accommodate the old man’s eccentricities. He hates to have anyone hear his original compositions. He didn’t know they could be heard from below, and will pay for the narrator to live on a lower floor—although he promises to invite him up sometimes.

Once the narrator has removed to the third floor, he finds that Zann’s eagerness for his company vanishes—indeed, the old man makes every effort to avoid him. The narrator’s fascination with Zann’s music continues, and he sometimes sneaks up and presses his ear to the door where he can hear the evidence of the man’s genius. It’s difficult to believe that a single viol could produce such otherworldly, symphonic tunes.

One night the music of the viol swells into a chaotic pandemonium, broken by Zann’s inarticulate scream. The narrator knocks and calls out. He hears Zann stumble to the window and close it, then fumble with the door. The man appears genuinely delighted and relieved at the narrator’s presence, and clutches at his coat. He draws him inside, writes him a swift note, then sits to write further. The first note implores him to wait while Zann writes a detailed account of the marvels and horrors that he has encountered—an account that presumably explain the mystery behind his music.

An hour later, still writing, Zann stops and stares at the window. A single unearthly note sounds in the distance. Zann drops his pencil, picks up his viol, and commences the wildest music the narrator has ever heard from him. It’s clear, watching his face, that his motive is nothing other than the most dreadful fear. Zann plays louder and more desperately, and is answered with another, mocking note.

The wind rattles the shutters, slams them open, shatters the window. It whips into the room and carries Zann’s scribbled confession out into the night. The narrator chases after, hoping to recover them—and finds himself staring not over the city, but into interstellar space alive with inhuman motion and music. He staggers back. He attempts to grab Zann and pull him out of the room, but the man is caught up in his desperate playing and will not move. At last the narrator flees—out of the room, out of the house, down the Rue d’Auseil, and at last across the bridge into the ordinary city. The night is windless, the sky full of ordinary stars.

He has never since been able to find the Rue d’Auseil—and does not entirely regret either this failure, or the loss of whatever terrible epiphanies might have been offered by Zann’s lost confession.

What’s Cyclopean: Tonight’s musical selection is cyclopean-free. We do have some very nice insanely whirling bacchanals for your listening pleasure.

The Degenerate Dutch: Ethnic backgrounds are described fairly straightforwardly—but both Zann’s muteness and the landlord’s paralysis seem intended as indications of the Rue d’Auseil’s inhuman nature. Awkward.

Mythos Making: Ever heard of something that plays mad, unearthly music in the center of interstellar space? Seems like it rings a bell—or a mad, piping flute.

Libronomicon: No one’s sure why, but the music section of Miskatonic’s library has really good security.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The narrator implies, but doesn’t state outright, that he may not have been entirely in his right mind during his sojourn on the Rue d’Auseil. And Zann’s music—though notably not Zann—is repeatedly described as “mad.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

When Zann sits down to write of the wonders and terrors he’s encountered, you think you know where you are—now, as in “The Mound,” we’ll switch to the testimony of a direct witness to the horror, and leave the narrator hoping desperately that he’s read the ravings of a madman. Instead the memoirs go right out the window, along with the usual Lovecraftian Tropes.

The loss of any detailed explanation—whether fantastic or science fictional—isn’t the only way this story stands out. The narrator knows the dangers of scholarship and knowledge: certainly something about his metaphysical studies has driven him to the Rue d’Auseil. But this is a story about the temptations and dangers of art. The narrator confesses himself ignorant of music, and Zann is clearly a genius—of what sort, let’s leave unsaid—but they are both swept up in its power, as creator and as audience.

Now I know you’re all asking yourselves: what’s an Auseil? It’s not any French word. It’s uncertain whether that reflects Lovecraft’s ignorance, or a play on “assail,” or whether there’s someone of the name “Auseil” after whom the street is named. Though it’s intriguing to speculate what type of person gets a street like that named after them.

What’s actually in that abyss that Zann guards? Lovecraft seems to have made a deliberate attempt not to fully reveal his horrors here. But this isn’t the only time he portrays mad music in the cold of space. Is this one of the familiar horrors of the Mythos? Or are the similarities only coincidence? If one accepts the former, one is left with the fascinating question of how Zann attracted Azathoth’s attention—and what kind of tenuous power he’s managed to acquire against that primal force.

The street itself is in some ways more intriguing than the view out the window. Its steepness and strangeness bar ordinary traffic. It’s a liminal zone, not fully part of the ordinary city, nor quite fallen into the abyss that lies beyond its crowning wall. It’s inhabited by the aged, the sickly, the disabled. Are these meant to be people who also don’t quite fit in either realm? If not, why not? The modern mind isn’t entirely comfortable with that type of relegation—but that doesn’t prevent modern society from likewise pushing such people to its edges. And the narrator has an insider’s view of the street rather than an outsider’s: poor and suffering from the psychological and physical effects of his studies, he’s not in a position to judge his neighbors and for the most part doesn’t attempt to do so.

Zann falls into the same interstitial space. We don’t know whether he became mute as a result of staring too long into the abyss, or whether he was able to contact the abyss because he was forced to find new ways of communicating.

As I read through these stories, I’m finding some of the knee-jerk bigotry I expected—but also some surprising moments of self-awareness. I’m not entirely sure where this story falls on that spectrum.

Anne’s Commentary

For a second week, by chance or some mocking intervention of the Outer Gods, our story features a German character. How different from Karl, paragon of Prussians, is poor Erich Zann, diminutive and bent and satyr-featured, of no more respectable a profession than theater fiddler, afflicted with muteness and manifold nervous tics. Yet there are crucial similarities. Both men are stranded in extraordinary circumstances. Both hear the music of outré spheres. Both attempt to leave accounts of their experiences. Karl’s bottled manuscript finds readers, but it’s necessarily truncated, missing the end he meets when he’s gone beyond means of communication with his fellow—living—men. Zann fares worse: His narrative is whisked beyond human ken in its entirety.

I register no premonitory tremors of the Cthulhu Mythos here, as I did in “The Temple.” “Music’s” poetic tone and pervasive nostalgia put it more in the Dunsanian range of Lovecraft’s influence-spectrum. The Dreamlands echo in its uncanny strains, and I wonder if the Rue d’Auseil isn’t a point of departure akin to the Strange High House that’s Kingport’s most charming landmark.

Central to this story is one of my favorite fantasy tropes, the place that is sometimes there, sometimes gone beyond rediscovery. Which brings us to our narrator, who is not Erich Zann, for then Lovecraft could not fairly have concealed the mysteries of his music. Instead we get an unnamed student of metaphysics, attending an unnamed university in a city I could have sworn was Paris; rereading, I see that Lovecraft avoids naming the city, too. There are boulevards, however, and theaters, and the lights burn all night, as one would expect in that metropolis. At the end of his meager resources, our student happens upon exceptionally cheap accommodations in a precipitous street but a half hour’s walk from the university. Or perhaps there’s a price as steep as the climb to be paid for his room and board.

The most striking feature of the Rue d’Auseil, this read, was how it’s a haven (or last resort) for the damaged. The narrator tells us his physical and mental health were gravely disturbed throughout his residence. Though the phrasing is ambiguous, I’m assuming he brought at least some of his ailments with him. All the inhabitants are very old. The landlord Blandot is paralytic. Zann is bent and mute. The ancient house in which the narrator lives is itself “tottering,” and other houses lean “crazily” in all directions, while the paving is “irregular,” the vegetation “struggling” and grayed. In fact, the only resident who’s described without reference to great age or sickness is the “respectable upholsterer” who has a room on the third floor, and any respectable person who’d deign to live in the Rue d’Auseil must have something wrong with him. It’s no place for the hale and hearty. In fact, I bet the hale and hearty could never find it or be aware of its existence.

It could be simplistic to view the Rue as a mere (if complex) metaphor for debility or madness, a diseased state of mind. Bump it up a fantastic step: It’s a place only the ailing can enter, prepared for the passage across the shadowy river and up the narrow cobbled streets by their suffering. They see things differently. They have altered sympathies, as in the narrator who says that his own sickness makes him more lenient toward the strange Zann. He also says that metaphysical study has made him kind—broadened his perceptions perhaps, opened his mind to less common conceptions of the universe?

Someone once told me, attributing the idea to Dostoevsky, that even if only the mad can see ghosts, that doesn’t mean the ghosts aren’t real. (Dostoevsky or ghost fans, point me in the direction of the exact quote, if it exists beyond the Rue d’Auseil!) My own idea here being that a certain degree of madness or (more neutrally) altered or unconventional consciousness might be a passport to the Rue.

The Rue itself appears to be a way station to wilder destinations, to which only a few may ever find passage while the rest of the “candidates” wither away, caught between the mundane and the beyond-places. Only one room on the street has a window that overlooks the high wall at its summit, and Zann is its current occupant and both terrified by and jealous of the privilege. What puts Zann in this position? He’s a genius, able not only to hear the music of the spheres but to give it an earthly-unearthly voice. Music is his voice, after all, since he cannot speak. Our metaphysician narrator may be another candidate for the top spot—clearly he’s drawn by music that’s the acoustic equivalent of Lovecraft’s non-Euclidian geometries, and by that tantalizing curtained window. So much drawn that he pauses, even in the climactic emergency, to finally look out.

To see what? Blackness and pandemonium and chaos, “unimagined space alive with motion and madness and having no semblance to anything on earth.”

Cool. So cool. Except maybe for whatever it is that’s been responding to Zann’s playing, that has rattled the curtained window, that gives the narrator a chill brush in the dark just before he flees the house and the Rue d’Auseil. Was his giving in to fear at this point equivalent to a failed audition, and the reason why he can never find the Rue again? What’s certain is that he semi-regrets his loss both of the place and of the narrative Zann was writing before weirdly sentient winds sucked it away (fore-echoes of the Elder Things!) He keeps searching for the Rue, and if he’s not “wholly sorry” for his losses, that means he’s not wholly glad, either. The terror and lure of the weird, yet again.

Join us next week for an allegory about the dangers of water pollution (or not), in “The Color Out of Space.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She bakes excellent chocolate peanut butter brownies, if she does say so herself.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available June 24, 2014 from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

The narrator lived there. So all his meager resources were there. The fact that no one has heard of the street proves he has never invited any friends there either (to listen to this strange music for instance), so I wonder if he had any, and if anyone was able to help him after his home disappeared.

I was looking forward to the French equivalents of « The Temple » German stereotypes, and I was disappointed. The representation of muteness certainly wasn’t good, but I don’t think it is there to appear inhuman: had Erich Zann not been mute, he would have explained what was happening rather than writing it down, and the narrator would have understood part of the mystery. The landlord paralysis is weird though. No mention is made of an elevator (the narrator climbs the steps to get to the fifth floor), so it seems he never goes to the upper floors : I don’t understand how he can manage the building.

Even though the narrator claims it’s for the best that he never could find the Rue d’Auseil again, it’s clear this adventure left him wanting for more despite the danger. We’ve encountered characters who had already took parts in other stories, so it’s not unheard of, but it’s the first Lovecraft’s story I’ve read where the narrator seems to be partly glad of what happened to him. Zann on the other hand, even though he’s not explicitely described as mad, clearly isn’t balanced.

I don’t see what’s so special about this street, apart from the fact it disappeared : I’ve seen stranger architectures. The word « oseille » does exist, but it seems the name of the street comes (as often) from the surname Auseil, which has disappeared nowadays. We can start speculating about what happened to these people, since the most probable explanation is boring.

In my memory of the story, I didn’t much care for it, but this time around I found that I really liked it. Perhaps because I wasn’t really looking for the mythos aspects this time and was simply willing to take it as it is.

I get a very strong Robert W. Chambers vibe from this one. I don’t know if HPL had already discovered Chambers at this point, but it feels a lot like some of the King in Yellow stories (“In the Court of the Dragon”, say). That would put it on the boundary between the Dreamlands and Mythos tales (though there are other stories there as well). And for absolutely no textual reason, my gut instinct is that Zann’s mysterious visitor is a nightgaunt.

ST Joshi has suggested that Auseil is derived from au seuil, meaning at the threshold. That does fit the story rather neatly. It’s an interesting theory at least. I have no idea what foreign languages Lovecraft was exposed to/studied to any degree.

I like the abstract vague horror here. Nicely done in an abstract horrific sense.

Of note also is that Mo’s violin from the Laudry Files by Charles Stross was made by Eric Zahn.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 2 I think of the visitor at the window as a nightgaunt, too. I’m reminded of the knocker at the door of the Strange High House, which the owner doesn’t admit and which afterwards hovers at the dim windows, a “queer black outline.”

The “au seuil” explanation for the street’s name is an intriguing idea.

DemetriousX@2:According to Wikipedia, Lovecraft read The King in Yellow in early 1927.

I had a very similar reaction to you, also, and it seemed of a similar twist.

@5 Stevenhalter

If that’s the case, then there can’t be any influence, since this first appeared in 1922. I would say that perhaps they were working from the same tradition, but Chambers also wrote other stories using the “student in Paris” motif, most likely because he had lived as a student in Paris himself.

Also I had forgotten that detail about Mo’s violin. For me the most salient feature has always been the “This machine kills demons” sticker.

This is, for me, one of the highlights of Lovecraft’s early career. I would side with those who think that there’s a Dunsany influence there, though mysterious goings-on in Paris (or somewhere like it) might imply this is a case for Auguste Dupin… One thing I like here is that there seems to be a full explanation from Zann, it’s just that the narrator doesn’t get to read it. And, of course, that moment when the musician becomes the instrument… It may be of some interest that Azathoth first “appears” in Lovecraft’s fiction in the June 1922 fragment of the same name, though he had had the word since 1919.

@anne, I knew there was a reason I kept Crime and Punishment lying around! Chapter I Part IV: “I agree that ghosts appear only to the sick, but that only proves that they are unable to appear except to the sick, not that they don’t exist.” I wonder if madness in Lovecraft’s universe generally lets you see things the sane have trained themselves to ignore?

@2: I like the “au seuil” idea in this context. I wonder if there’s any meaning behind the name of Erich Zann?

Weird Tales round-up: The first reprint was in the May 1925 issue, where it could be found alongside Frank Belknap Long’s “Men Who Walk Upon the Air”. It appeared again in November 1934, with August Derleth’s “Feigman’s Beard” and the third part of Robert E. Howard’s “People of the Black Circle”. This story got some further recognition in Lovecraft’s lifetime; it’s also in the 1931 Dashiell Hammett anthology Creeps by Night: Chills and Thrills.

Well, I’ve just learnt the origin of one of Charlie Stross’s little references.

In the Laundry Files books (which you will probably enjoy if you’re familiar with Lovecraft) Mo uses a violin which is described as:

Lets just say, it’s not the sort of instrument you’d play lullabies on…

As a further note from Charlie:

So, I suspect that we aren’t the only ones who have noticed the style similarity in this story and in Chambers’ works.

@5, @7: I seem to remember that in one of his letters Lovecraft wrote that his inspiration for this story came from a dream he’d had of wandering the streets of Paris in the company of Edgar Allan Poe.

@10:That’s interesting. I could see how channeling Poe and Dunsany could lead to this very sort of tale.

@7 SchuylerH

What does Shaenon Garrity call it? Reality filter, reality blindness, something like that.

As for the name Zann, it’s a real name, but I have no idea of its origin or meaning. It looks like the best known person of that name is an actress/politician who is best known as the voice of Rogue in the 90s era X-Men.

Re Mo’s violin, I’m looking forward to a story from her perspective. It will be interesting to see Bob from the outside.

I’m glad I reread this story as my memory had completely altered the text. For some reason I had Erich Zann writing something akin to “Gloomy Sunday” which if you read the background of that song it comes off very Lovecraftian. Fortunately I did still enjoy this story.

When I was reading this story I didn’t get the sense that the Rue itself was mystic, in that it could only be found at certain times or by certain people, instead I got the impression that it had been altered. Maybe once it had been a quaint little street with nice people when it drew the attention (or at least the presence) of something beyond. Maybe Zann was experimenting with some new form of music and that’s what got the whole thing started. As whatever was on the other side drew closer to our dimension, the street began to change into a twisted version of itself and the people with it. Zann stays and plays his music to try to hold the creature back (maybe it has something to do with Zushakon from Kuttner’s Bells of Horror) but it is ultimately a doomed quest. In my mind the narrator is drawn to the Rue because he may have brushed with the other side in his metaphysics studies.

Also it seems like this is how the song “The devil went down to Georgia” should have ended.

@10: The source of that claim is Jacques Bergier, who claimed to have corresponded with Lovecraft. Unfortunately, HPL never mentions Bergier anywhere, and no letters between them seem to exist, so the “in a dream with Poe” thing is suspect at best.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 7, DemetriosX @@@@@ 12: I’ve noticed that there are a lot more people in Lovecraft claiming to be mad or worrying about being mad, than actually being mad. Often they hope that they’re mad because the alternative is that what they’re seeing is real. So it’s less that madness makes you see things, and more that madness is a first go-to explanation for seeing things. Iffy here, but definitely the case in Shadow Out of Time and several others.

StevenHalter @@@@@ 9: That’s awesome news, thank you for sharing. The Laundry books are one of my favorite modern takes on the Mythos. And yes, Maureen’s violin is deeply alarming.

@12: I wonder if Zann is a version or relative of Zahn, which reputedly derives from the Middle High German “zan”, or “tooth”. (Charlie Stross uses Zahn in the Laundryverse) This may be a little fruitless but it reminded me of Heir to the Empire for a while, so there’s that…

@14: Is that the Jacques Bergier of The Morning of the Magicians? Because if so, I would be strongly disinclined to trust anything he said.

@15: I got thinking too much about fnord again, didn’t I?

As an aside: does anyone now want to see an F. W. Murnau version of this?

SchuylerH @@@@@ 16 Re Murnau version, definitely, complete with all appropriate Nosferatuesque shadows.

@16/17

Or possibly Robert Wiene.

The Dostoyevsky quote you’re thinking of is from one of the characters in Crime and Punishment – I remember it because I just finished the book a week or so ago.

Reading this story, I wondered if Zann somehow found himself the guardian of the Rue d’Auseil – that perhaps his music was all that kept those otherworldly forces from overtaking it. Maybe, once he finally lost the fight and died, the Rue d’Auseil was gobbled up into that abyss, which is why the narrator was never able to find it again.

Of course, I read the story as someone not very familiar with Lovecraft’s larger mythos, so take any hypotheses I might offer with whatever size grain of salt seems appropriate.

-Andy

Actually, Zann derives from one of the characters in ETA Hoffman’s tales, a story about a young man, a young woman with a respiratory disease and an unearthly, beautiful voice, and the young woman’s old, protective father. Zann is the father, transmogrified.

What transmogrifies him is the city: he watches over the Threshold: the wall which his window overlooks. So we still have the young man, but the city is the beautiful girl, with the respiratory disease.

And this time, it’s the protective father who dies.

@8. phuzz

I want one. Oh God, how I want one!!! Where can I get it?

@7/16 Schuyler, @12 DemetriosX

re: meaning of Zann

There might be a connection to the German surname ‘Zanner’ which is derived from the Middle High German verb ‘zannen’ meaning

a) ‘to snarl/growl, to cry, to wail’

b) ‘to open one’s mouth wide, baring one’s teeth’

or the Middle High German verb ‘zanen’ meaning

a) ‘to bite, to grab with one’s teeth’

b) ‘to chafe’ in the broader sense of getting hurt by something.

I can see sort of a loose metaphorical connection to what Erich Zann is doing, but I think it’s most likely a coincidence. Middle High German disappeared in the 14th century and this particular verb with it. Unless it’s an odd piece of trivia HPL picked up somewhere I don’t see that ending up in the story on purpose…

Of note also is that Mo’s violin from the Laudry Files by Charles Stross was made by Eric Zahn.

Mo plays a violin, and, until I read this post, I could have sworn that Erich Zann played one too. And you can see it, can’t you: the mute, wild-eyed German exile, swaying frantically, hair flying as he throws all his energy into playing. Imagine an insane Jascha Heifetz or David Oistrakh. There’s something unsettling about a really good violinist.

But it’s a viol – a much bigger instrument, played between the legs like a cello.

Somehow that’s just not as unsettling. I can’t really lever the words “eldritch” and “cello” into the same mental pigeonhole. He’d have to sit down to play it, for a start.

@21: Do you happen to know which Hoffmann story that was? There are very few Zahn violins in the Laundryverse and Mo doesn’t technically own hers. It’s made of bones extracted from living humans and, as such, is not suitable for most normal music, though it can return the walking dead to the grave and create storms. Still want one?

@23: I know, I prefer a violin too (just look at the page image). I rather like the Stross perspective, where Lovecraft is something of an unreliable narrator.

It’s interesting, in Laundryverse terms, that Mo is now the narrator. I remember Stross said that he would have to change the perspective to prevent the Honor Harrington problem…

@23 a1ay

I like the image of Zann playing a cello. The movements are grander with both the instrument’s neck and bow being much larger. Also there is the idea of being pinned down by the instrument. With a violin you’d have the option of retreating while playing. With a cello you have to stay and play, any sort of retreat is impossible because you’d have to stop playing…

But then I have seen Apocalyptica play and that might have had a certain impact…

Just a tidbit – this was the only Lovecraft tale Robert Aickman liked (or, to quote him, “quite” liked).

Sounds like “The Cremona Violin” (aka “Councillor Krespel”).

Q: I am a fictional character and I play a musical instrument. Can my instrument credibly be used as a method of summoning, controlling or dispelling eldritch forces without seeming silly to the reader?

A: Musical instruments fall into three categories when it comes to their credibility vis-a-vis the occult.

YES, DEFINITELY:

Pipe organ

Violin

Harp

Gong

Drum (kettledrum, Japanese taiko drum in particular)

Flute or pipe

Theremin

Trumpet

WELL, MAYBE, I GUESS

Cello

Oboe

Zither

Drum (side, military)

Piano

Bagpipes

Guitar

OH, HELL NO:

Tuba (yes, Tuba mirum spargens sonum/ Per sepulchra regionum/Cogens omnes ante thronum. Very clever. You know what I mean.)

Glockenspiel

Kazoo

Trombone

Drum (snare)

Mouth organ

Double bass

Guitar in the well-maybe-I-guess category? Whatever happened to “rock’n’roll is the devil’s music”? Haven’t you seen the entirely and 100% factual documentary “Tenacious D in: The Pick of Destiny”?

Guitars are without a doubt THE go-to instruments for any summoning-, controlling- and dispelling-related activities…

“The Kazoo of Erich Zann” .

Want.

What Anne & Ruthanna, no comments in the pre-comments about the tangent the comments went on last week? Darn. I was hoping one of you would say something about it.

Looks like we have already started on a great musical instrument tangent.

@28: Great listing. I have to agree with them all, yet I now want a story about a possessed Tuba. Especially a marching tuba. It does already wrap around you and can become quite burdensome.

Schuyler @@@@@ 7 and KatherineW @@@@@ 19 Thanks for the Dostoevsky reference! Been bugging me for a while. I love (storywise especially) the idea that altered consciousness (through illness as well as whatever) could bring altered perception that is not necessarily false.

a1ay @@@@@ 28: Agree with list, except for the double bass. That deep throaty voice is so powerful, and you could actually store your summoned familiars inside it. The ukelele, on the other hand, would only summon the peskiest yippy-dog analogs among ethereal servitors.

Braid_Tug @@@@@ 31: My comment is much is learned from the tangential. Indeed, the tangential mixed with the serendipitous makes the best feed for the plot bunnies in the hutch.

@32: What if Jack Vance was playing the ukulele? (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oiOt6eW0pZI)

Lots of good comments above. “The Music of Erich Zann” seems to me one

of the more enjoyable of Lovecraft’s earlier stories–neither Cthulhu Mythos,

New England horror, nor Dunsanian, but certainly anticipating the cosmic

quality that permeates much of his later work.

The story’s most interesting detail for me is its invocation at the

beginning, and again at the end, of the device I’ve come to think of as the

“disappearing place.” In “Zann,” it’s a street and neighborhood that

disappears, but this is not HPL’s only story using this motif. It is

prefigured by the disappearing cavern in the ending of “The Transition of Juan

Romero,” and repeated by the underground laboratory that ceases to exist in

“The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.” This seems to be physically implausible,

and in “Romero” and “Zann,” we are given the option to suppose that the

narrator has hallucinated the occurrence. However, in “Ward,” the vanishment

is presented as an objective event. I’ve never felt clear about Lovecraft’s

intent in this device, but in “Ward,” it seems to demonstrate that necromantic

wizardry is able to alter physical reality, thereby emphasizing the extreme

danger that has been averted when the warlock Joseph Curwen is destroyed.

Back to the climax of “Zann”: “…I felt the still face; the ice-cold,

stiffened, unbreathing face whose glassy eyes bulged uselessly into the void.”

Zann’s playing was so obsessive that he kept at it after he was dead: a

preview of the animated corpses in “Cool Air” and “The Thing on the Doorstep.”

Schuyler @@@@@ 33 I will have to subject the video to extensive hyperdimensional analysis before I can answer your query.

DGDavis @@@@@ 34 As someone who often walks along the Pawtuxet River, where Curwen’s farm was located, I’m not at all sure his subterranean lair has disappeared. Curious disembodied voices and croakings sometimes trouble this area, seeming to come from beneath the earth….

@Squamous Gambrell: Stross gives passing references in the early Laundry tales that making a Zahn violin qualifies as a crime against humanity; he gives a more complete description of the construction process in The Rhesus Chart, plus what playing one does to the musician; trust me: you really, really don’t want one.

Guitar in the well-maybe-I-guess category? Whatever happened to “rock’n’roll is the devil’s music”?

And, for that matter, the blues, for the secret of which Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil. Good point. Maybe “guitar” gets bumped up to the premier league.

30: it is, I suppose, conceivable that the mindless, incessant piping associated with Azathoth the Blind God is in fact the noise of a Swanee whistle. An example of what the combination would sound like is here. Listen – if you DARE.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9mNBsEDr98

A few years ago, we took a cruise in the Greek isles and I was amused by various places catering to German tourists inevitably having Oompah bands live with at least one tuba player. Having one of those devolve into a summoning of eldritch horror would not really surprise me.

@37: It’s horrifying! Yet, I can not look away! Save yourselves!

(http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MzmPGNKopc)

I’m not going to go back and tag everyone on these comments.

Re the name, I’m in agreement that any possible appropriate derivation of Zann is a coincidence. Lovecraft seems to have largely played his character names by ear, rather than loading them with symbolic significance. I suspect he just went looking for a German name and found one he liked the sound of.

Instruments: I agree that the viol doesn’t really seem to fit. The way Zann turns to the window in the climactic scene also seems to contradict an instrument played while sitting. I wonder if Lovecraft had confused the viol and the viola. It’s a not uncommon mistake, since the viol is also known as the viola da gamba.

I’m also in the camp for moving the guitar to the YES, DEFINITELY camp. Apart from the various metal subgenres, I would point you toward Tim Schafer’s Brütal Legend. The electric guitar is really the modern go-to instrument for all your occult needs.

This is certainly the most useful categorization method for musical instruments that I’ve ever seen. Or at least the most entertaining. Agreed about guitars, especially electric guitars.

The viol -> violin transformation appears to be universal. Not only Stross, but every illustration I found, has something a bit more portable. Narrative imagery has its own momentum.

In Jinx High the villain summons demons to possess electric guitars. She makes a mistake with the last one and accidentally summons the soul of a hippie, which later fights the music of the demons (with the help of the good witch).

I might have to move Drum (side, military) up to YES, DEFINITELY as well, because presumably this would include Drake’s Drum, which actually exists and has the power to summon a Zombie Pirate Army to defend the English Channel in time of need (YES IT DOES SHUT UP) as well as sounding by itself whenever something adequately victorious and naval happens to Britain.

@44

I think drums in general probably belong in the top category. You’ve got Siberian shamans drumming to enter the spirit world, drum circle induced trances, I think voudoun trances to summon the loas are induced through drumming, even drumming occurring during seances.

The story is one of those captivating fables that may or may not be dream. It is so alluring that the narrator, having fled the realm with “leaping, floating, flying,” is then obsess’d with finding that haunted realm once more. Brilliant!

The main influence here is definitely Chambers, both thematically and in stylistic detail. Eg., compare Zann to the “Repairer of Reputations”, which was Lovecraft’s all-time- favorite story.

@16: Yup, that’s the guy.

@47: The Chambers influence can easily be dismissed as impossible and that has already been done further up. “The Music of Erich Zann” was written in December 1921; Lovecraft didn’t read Chambers until 1927. Also, Lovecraft’s all-time favourite weird story was “The Willows” by Algernon Blackwood.

Getting this one in before the estimable @MTCarpenter does: a younger, talkative Erich Zann from that pinnacle of sequential art, Afterlife With Archie #6: http://afterlifewitharchie.tumblr.com/post/93449648036/thelibraryofcalebxandria-erich-zann-from-h-p#notes

You may be wondering whether Cthulhu appears in this comic. The answer, it seems, is yes, yes he does:

http://afterlifewitharchie.tumblr.com/post/93059178621/punkhead66-cthulhu-is-awesome-in-afterlife-with#notes

In my mind, I associate this story with Jean Ray’s “The Shadowy Street” and China Mieville’s “Reports of Certain Events in London,” which both deal with streets behaving strangely. I tend to enjoy stories like this where the weirdness doesn’t necessarily get explained away, but is the driving force of the story. It’s much creepier this way.

Ray’s story looks like it was published in 1931. Any idea if he had any influences from Lovecraft?

“Ray’s story looks like it was published in 1931. Any idea if he had any influences from Lovecraft?”

I don’t think he read English, and Lovecraft wasn’t translated then.

@50 – Alas my post this week was flagged as spam. It may show up here in a few days.

Ladies, especially Ms Emrys –

you have not read Joshi and Schultz’ Lovecraft Encyclopedia yet by any chance? ‘Auseil’ is explained there as being a speaking name, derived from ‘au seul’ = “at the threshold”, and Mr Zann certainly dwelt at the threshold of something unearthly, whatever it was…(Joshi & Schultz, 2001: 178).

As for Mr Steve Halter’s comment regarding German tourists and Greece and oompah bands – well, I have certainly met a considerable number of fellow countrymen on my travels who would match every aspect of your average caricature German, for the better or the worse – but rest assured, dear Sir (and do I detect some German origin in your own surname?), that there are German tourists, and travellers, who would object to oompah music in Greece or elsewhere in the Mediterranean, and who would prefer other music – I for my part prefer traditional Irish and Scottish music, or 1920-30s Jazz, or trad Country&Western, or classical music…the latter especially suitable for a steamer off the Greek coast, I should say – or the Savoy Orpheans, or Jack Buchanan or Jack Payne or Jack Hylton for some decent ballroom music! I am certain one Mr Algernon Blackwood would agree to that…but pu-leease, Mr Halter, unless you were taking the mickey, your ethnic stereotyping would be as awkward as the late Mr Lovecraft’s!

Kind regards,

a Scottish-based German gentleman scholar and author

Fear Araltsaigh@54:No stereotyping on my part, I didn’t mean to imply that all Germans like Oompah music. I’m sure there are many that don’t.

Oompah music is far from the most heinous of Germany’s musical crimes. Indeed, when played by an enthusiastic village band it can even be enjoyable, as I have experienced (complete with shoe-slapping, bench-rattling dancing). But much like Mariachi (which has oompah in its DNA), it can be truly terrible when performed by those who don’t have an inherent knowledge and understanding of the genre (for example, a group of Greeks hired to play for German tourists).

No, far worse are things like Schlager (which simply means “Hits”). Now, from some decades Schlager are quite tolerable, but for the last 30 or 40 years they’ve been pretty awful, with a focus on Moon/June/Spoon rhyme schemes (or Herz-Schmerz as it is known in Germany). Imagine a genre populated by degraded copies of Barry Manilow and Dan Fogelberg. Stuff that, if you control the music, you’ll switch off immediately, but if you can’t (say at a restaurant), you don’t want to jam icepicks in your ears.

Worse still is Karnevalsmusik, with its simplistic tunes and ridiculous lyrics, all intended only to be enjoyed when in a highly drunken state meant to leave you with a hangover that will last for most of Lent. Closely related is what they call Ballermann, which is intended to be bellowed by large crowds of very drunk German tourists. It often samples classic rock songs such as “Hey! Baby”, just repeating the chorus over and over.

But the true mind-destroying, soul-devouring horror, the gibbering and wailing chaos at the heart of the universe, is Volksmusik. This is not, as you might suspect, folk music (that would be Volkslieder). It’s a sort of sanitized, highly processes faux folk, dressed up in Dirndls and Lederhosen, such as might have been seen on Lawrence Welk. Only more soulless. When I first moved to Germany 15 years ago, Volksmusik shows were everywhere on TV, inescapable. The genre is slowly dying, thank God, and few Germans below retirement age hold it in anything but contempt, referring to the bands and shows with rude and crude names not printable on a family website.

The land of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms has fallen far, musically. But oompah is the least of its horrors.

Musical horrors never die, they only sleep, dreaming, until the stars (or reality TV opportunities) are right.

@57

Oh God, you’re right. German hipsters could start listening to it ironically. I… I hadn’t considered that.

48: well, dang, live and learn. Yer right, it was 1927.

@57 DemetriosX

If they ever do, I hope someone punches them in the face. Ironically.

Perhaps relevant to certain aspects of the discussion:

http://www.antipope.org/charlie/blog-static/2014/12/a-message-from-our-sponsors-7.html

Hello. About Mo’s violin, it seems that it has brothers in the real world (maybe). Follow the link: http://www.siegmundguitars.com/violectric.html

Zann plays three types of music in the short story.

1. The haunting, weird music that awakens the narrator’s curiosity, but which Zann does not want him to hear.

2. Original compositions by Zann, without the weird harmonies.

3. A Hungarian tune known to the author as by another composer.

My theory is that Zann invents the first type of music, and finds that it attracts something otherwordly to his window. Curious about this, he keeps playing this music almost compulsively, letting the other dimension approach closer and closer. He is however secretive about his designs and does not want anyone else to know about them, or to repeat the melodies (he wants to find out for himself first), which is why he plays original compositions without these weird harmonis to the narrator, and forbids the narrator to whistle the tunes. He also does not want the narrator to peer out the window and see what has started to take shape because of Zann’s musical experimentation.

Then one night, Zann realizes while playing his weird melodies that he has been summoning something evil or bad, cries out and faints. When he wakes up, he shuts the window and is relieved to find the narrator, whom he know intends to tell the whole story, most probably as a warning, now that he knows what it actually is he was summoning. Mute as he is, he is writing this down, when musical sounds are heard from the window. Anxious that whatever evil was summoned last time, is this time coming back without any summoning, he rushes to his viol and plays this Hungarian folk music in order to drown out the other sounds, or at least he is hoping to ward off the evil that is coming, by playing something else than the ‘summoning music’.

He fails, and darkness engulfs the whole street, swallowing it into another dimension, erasing it from history, with only the main character escaping.

I believe one of the most likely source for this short story is a Maupassant’s one titled “Who Knows?”. The same atmosphere, almost identical description of the old french street. Moreover, Lovecraft mentions this story in Supernatural Horror in Literature.

i know this is posting many years after the original review, but for anybody who thinks the cello is necessarily an instrument that must be played while confined to a chair, i’d encourage you to google “Rushad Eggleston” and watch a few videos of his performances :). he’s a friend of mine and although in lovecraft’s time there probably weren’t too many celloists in his vein, it IS indeed possible to perform wildly and acrobatically with the instrument.

I’ve always wondered something about this story.

Lovecraft wrote in English, not Americanish. In English, the floor of a building at ground level is the ground floor, and the one above that is the first floor. But Lovecraft was an American, so did he number his floors in English or Americanish?

According to Google Translate, auseil means “to escape” in Frisian, Luxembourgish and Hebrew, “absent” in Spanish, “austerity” in Amharic, Somali, Yoruba and Hausa, “water” in Bengali, “asylum” in Greek, and “means” in Urdu.

Mindlink @@@@@ 68: Wow, I count a possible quintalingual pun there! (Not sure the Urdu fits, but all the rest do.) That’s got to set some kind of record.