Thanks to editor Mal Frazier at Tor, who read the SFF Bestiary article on Moby-Dick and offered an early look at an upcoming novel, I have had a very pleasant end-of-year vacation reading Alexis Hall’s Hell’s Heart. The jacket copy calls it “Gideon the Ninth meets Moby-Dick,” and that’s accurate. It’s a bravura piece, following the plot and characters of Melville’s novel closely, but taking them in directions that are all its own.

There is so much to this retelling and recasting. Literary allusions in two languages and cultural traditions. Historical references. Worldbuilding that riffs, sometimes ferociously, off current events.

In the far future, the spaceship Pequod, which the narrator calls a hunter-barque, and its crew and its legendary captain, hunt Leviathans on and in Jupiter. Earth, or Terra, has been stripped of its resources and essentially abandoned. Most of humanity lives in space.

It’s a grand adventure. It’s also blessed (some readers might say cursed, but that would not be me) by Melville’s original structure, which puts the worldbuilding right out front, in dedicated chapters. We learn in detail what a hunter-barque looks like, what its parts are and why; we know what it’s doing out there, and above all, for the purposes of the Bestiary, what it’s hunting.

There’s a whole chapter called “Cetology.” Here we learn that

The broad class of beasts that includes the Leviathan, sometimes known as Titans and sometimes Cetaceans, includes four main categories of horror: Behemoths, Krakens, true Leviathans, and Wyrms.

These are the creatures we will meet, and the characters will hunt and fight and kill and be killed by. The category adds up to, at its simplest, “some great beast with chitinous mandibles and feeder tendrils.”

Behemoths are the biggest:

[…] armored maggots a kilometer long which move ponderously through an ocean of ultra-dense liquid star-metal.

They have no mouths, and some scholars speculate that they feed on the massive electrical energies generated by the currents within Jove’s liquid center.

The description makes me think of amphipods, though these small and abundant terrestrial creatures are not armored. The shape and overall structure are similar.

[Krakens] are nearly as big as the Behemoths, but less massive, if you see what I mean. They’re all tentacles and float-sacs, and most of the time they just blow whatever way the winds take them on long parachute arms. Once or twice, however, I’ve seen one expel a great jet of plasma from its rear end. Or its front end. Their body has a lozenge shape, and they’re studded all over with eyes, so the extent to which they can be said to even have a front and a rear is debatable.

They’re basically giant muscular bags full of gas, and however they turn atmospheric flotsam and any ships they might eat into usable energy, the organs don’t survive gutting.

That reads to me like jellyfish. Jellies are as alien as it gets on this planet, and I can see them making sense on Jupiter.

Wyrms are a different kind of animal, and ubiquitous in the story:

[…] invariably eel-like, invariably fly in the strange skies of Jove, and there their similarities to one another end. Some are as long as your finger and feed by skimming some unknown element from the surface of the hydrogen sea. Some are twice as long as your entire body and feed by biting chunks out of anything they happen to fly into. Some attach parasitically to Behemoths or Leviathans, some seem to hunt the ones that live parasitically. In a lot of ways it’s beautiful. If your idea of beauty revolves strongly around long thin monsters eating each other.

The narrator points out the analogy to eels, and to the remoras that surround various species of whales, as well as the parasites that infect the eyes of Greenland sharks. Wyrms are a fair bit like sharks themselves, in the way they’re always there, ready to swarm in toward any possible prey. A considerable part of the job of processing a kill involves fighting off Wyrms.

And finally, there are the true Leviathans, of which there are multiple species.

They’re all between some tens and some hundreds of meters in length, always far longer than they are broad and far broader than they are tall. Their flight, which like most Jovian creatures makes a complete mockery of conventional aerodynamics, is an undulating motion supported by rippling side fins which together make up perhaps half their body width. There’s also similarity in their tails, which are always long and taper to points.

Although we know these are the Jovian analogues of whales—both baleen and toothed whales—their anatomy, with the rippling fins and the sharply pointed tail, points toward another terrestrial species, the giant oarfish.

Finally, they’re always hydrogenically amphibious, able to exist both in the skies and in the hydrogen sea itself, although different species divide their time between those environments differently.

Of those species, the ones most relevant to the story are the Barnard’s or Slack-Jawed, which is the largest and least known, and which feeds on energy by swimming or flying along with its mouth wide open; the Death’s Head,

named for the skull-like armor plates that cover most of its head (all Leviathans are armored, the Death’s Head just frontloads it). Although its jaws are dangerous, its primary means of attack against large enemies seems to be ramming. This makes it a huge threat to hunter-barques, but since it feeds exclusively on the lesser Jovian creatures, smaller even than the Wyrms, scholarly consensus is that the head armor evolved for mating duels, rather than for hunting.

And finally, the real point of it all, the reason for the hunt and the whole epic adventure, the Ridgeback or Sperm Leviathan.

It takes its name (both of its names, really) from the long, broad ridge that runs the length of its spine. This ridge is filled with long bundles of nerve fibers, and those fibers themselves are bathed in the unique substance we call spermaceti. The creature’s brain is also marinated in the stuff. At least two scholars have suggested that this close neural connection to such a powerful fuel should grant the creature psychokinetic abilities, and one of those adds that this might help to explain how it (and by extension all Jovian creatures) can actually fly.

There are others, but these are the ones that figure in the story. The Ridgeback matters most of all to the universe it lives and is hunted in, because spermaceti powers everything in the human system. Without it, there’s no life support, no transport, no habitats, nothing. Everything relies on it.

That makes the Pequod’s mission vital. The crew sign on for a three-year voyage, paid by shares in the eventual profits, like terrestrial whalers. The ship becomes their world. They meet other ships occasionally, but for the most part they sail, or fly, through the Jovian atmosphere in search of the electrical spouts that mark the presence of their prey.

The hunt, the capture, the kill, proceed much as they do in Melville, with similar levels of both danger and tedium. Because this is Moby-Dick in space, the ship’s captain is spectacularly and epically fixated on the legendary (if not outright mythical) Möbius Beast. This Leviathan of extraordinary size, intelligence, and apparent malice robbed her of her leg, and she is dead set on revenge.

Leviathan anatomy, biology, and behavior are crucial parts of the story. Despite centuries of the hunt, no one knows a great deal about Jovian animals. It’s not even known to science how or when or where they breed, though hunters (if they should ever be asked) can answer some of those questions. The Pequod, like its terrestrial forebear, finds a breeding ground, and sees how Leviathans gather in family groupings, with females and young and the enormous males.

Scientists might study, but hunters hunt. The breeding ground is a bonanza. Hunters can pick and choose their quarry, hunt down and kill and process as many Leviathans as their equipment and their crew can manage. Conservation is not an issue, and preservation has no meaning. The human universe can’t survive without the hunt and the kill. There’s no alternative, as far as we know or the narrator will tell us.

Just as in Melville, the hunters don’t see the quarry as fellow sentients. They’re hunting monsters, creatures whose intelligence isn’t relevant, unless it happens to be hostile. Even there, that hostility or apparent malice may be no more real or intentional than the storms that buffet them or the gravity that pulls them down into the depths of the gas giant.

Hell’s Heart does a splendid job of capturing the spirit of Moby-Dick. A good part of that, and a great deal of the fun, is the range and variety of its fauna. Even though we know how it has to end, when we finally meet the Möbius beast, we’re there for it. We’re ready for that last, terrifying, fatally fascinating ride into the heart of Jupiter’s blood-red hell.

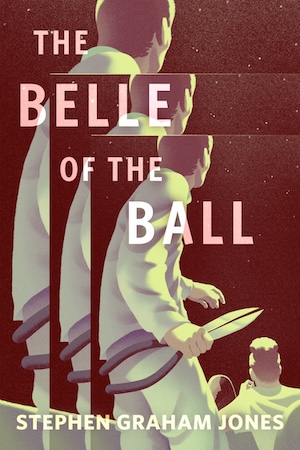

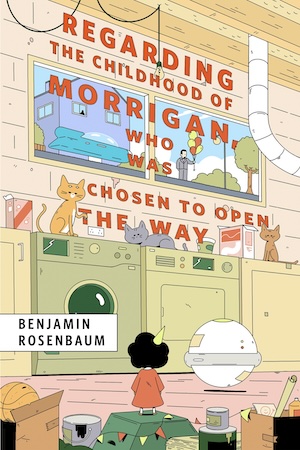

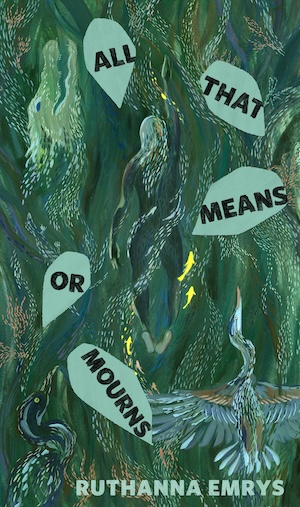

Buy the Book

Hell’s Heart