An older medic with scant resources fights to support her community as they survive life behind the company wall.

Novelette | 9900 words

A sharp report shocks Rose out of her sleep. Without sitting up, she rolls off the old cot, one hand pushing back so it doesn’t tip over onto her. Although her five years as a medic during the war happened decades ago, she’s never lost the training.

The gunshot had the distinctive gassy cough of the CM-70 used by company sentinels. From her knees, she scans the dark room with her old military inserts. Seen through infrared, the room’s outlines remain recognizable: table and chairs, sofa and lamp, cupboard and changing screen, the curtained alcove where her grandsons share a double bed once used by the boys’ parents—her son and daughter-in-law. The two sleeping forms create a blotchy intensity visible through the gauze curtain.

The ceiling fan turns in a slow grind, shifting the muggy air. Maybe the sound was merely another flashback in a lifetime of bad dreams. Her gut tells her otherwise. This might finally be the link they’ve been struggling to connect with for years, as long as the shot doesn’t mean the company already killed the messenger.

She rises stiffly, knees popping and crackling, and shuffles to the window. This time of year, she leaves it open to bring in circulation. Anything to break the heat. A scan of the dark sky turns up no movement, although she hears the high alarm call of a killdeer amid the island stacks and the pillars of the drowned city, stretching east toward dawn. There! A brief glimpse of its energetic flight over the water before it vanishes from sight.

The town sprawled haphazardly along the ragged shoreline remains lightless, powered down for the night. No one and nothing is moving except a solitary dull red figure on the sentinel tower overlooking the salvage yard. Two more sentinels join the first. That’s unusual. Maybe they heard it too. Maybe they are the shooters. If that’s so, then what were they shooting at?

Motion out on the surface of the water catches her eye. She zooms in with her implanted lenses. The company has never discovered her military inserts because, from the outset, they stripped comprehensive health care away, so there was never anyone to identify and report her augments.

A boat glides behind one of the island stacks, visible to her from this angle but not from the sentinel tower’s line of sight. The boat displays no engine heat, just two bodies working oars. Night salvagers. Usually they’d have put into shore before dawn could betray illegal activity to the sentinels. Is it coincidence they’ve stayed out so long? Or is their delay related to the shot? How will they get in safely, especially if the sentinels see them? There’s nothing she can do, not until the morning siren allows people to leave their homes.

She blinks off the inserts, rubs her scratchy eyes, and checks her old combat comms link in case by some miracle there’s been a breakthrough past the company’s total blackout. No pings, no static; all quiet, like the dawn. As long as they can’t communicate, and the only public legal record available is that of their employment leases, the company can speak on their behalf to the Neutral Zone, which lies beyond the company’s shore operations and inland enclaves.

She leans against the sill to study the scene. The sky lightens. The curve of the sun breaches the horizon. Elongated rays of sunlight spread gleaming stripes across the murky waters. The landscape’s hushed mystery shimmers with simple beauty, even here, even now, in this broken, fragmented world.

The morning siren cracks the silence with a shrill hoot, repeated three times. The tracker embedded in her shoulder buzzes. The work day has started. For the next fourteen hours, everything is on the clock.

She leaves the window open and goes out to use the hall toilet. Handprint first, to register the user—all weight, volume, and analysis of waste and wash water calculated by WasteNot! WantNot! LLC and added to the cost of rent. While she is peeing, her combat link gives a proximity shiver. The company turned off the comms transmitter and receiver, but even the company’s blackout can’t eradicate the link’s proximity alarm. In this case, the two-fold shiver signaling the approach of a friendly, another servicemember from the old federal army.

When Rose comes out of the toilet, LaChelle is waiting by the door for her turn. LaChelle is older than Rose, so old she grew up in the city before the rising waters took it all. A career army officer, she is now an eighty-year-old shoreline trash picker. She uses her picker to lean on as she clips a thank-you nod at Rose for the gift of food Rose left for her last night.

“Damn crow woke me up,” she says to Rose. “Did it wake you too?”

“Yes. That squawk always jars me.” They’ve developed a complex code to get around places in the buildings where there are cameras and listening ears.

LaChelle scratches the side of her right eye to show she’ll keep an eye out on her shoreline trash patrol for anything unusual that might wash up.

“Plenty of birds out,” Rose adds, and there are: a pair of wrens in the bushes, a grackle investigating a patch of scrubby grass, even a robin pecking along the ground. “Feels like their population is growing. Could swear I even saw a pair of owls out hunting over the water.”

“I’ll check their nest. Maybe they’ll have a fish we can share.”

“A fresh fish this time, we can hope,” agrees Rose. Neither glances at the surveillance camera hanging above the toilet door in a corridor where people may gossip while they wait in line. “A shame the last three fish were too poisoned to eat.”

“I heard yesterday out on Spearhook Point from one of the rakers that there was a catch down south that didn’t have to be thrown out,” says the colonel, not that anyone calls her that now that the country she once served no longer exists.

“The tide is turning,” Rose says. It was their catch phrase in the closing days of the war, although it tastes bittersweet now, given that they ended up on the wrong side of the border. It all happened so long ago that the boys have never known anything except company rule. We old-timers haven’t forgotten, she thinks with stubborn pride.

LaChelle gives what once-sergeant Rose still thinks of as “an officer’s nod.” “May we all be so fortunate. Have a blessed day.”

“Have a blessed day.” Rose echoes the company-mandated phrase.

By the time Rose returns to their room, the boys are up and dressed. Tai will be fifteen next month. Leon is eleven. They’re responsible boys. They’ve been through a lot, having sat vigil by their father as he died from a highly resistant staph infection three years ago. Best Outcomes! LLC refused to approve intravenous antibiotics because his work detail in the salvage crews wasn’t rated high enough to warrant the expense. Soon after Eddy’s death, the boys’ mother’s contract was renegotiated by the central office inland, the office no one in this town has ever been to, as there is no way to get there. Sela was required to leave town—and her boys—to teach in one of the hill enclaves whose communities demand in-classroom teachers. She gets leave to come home just once a month, although each time she smuggles home a discarded print book.

While the boys visit the toilet and wash their hands, Rose divides up two bean and barley burritos she received as unrecorded payment yesterday. The third she tucked into a little hiding slot out of the camera’s line of sight on the landing, for LaChelle, who can barely eke out enough credit for a tiny sleeping closet and a single meal per day at the town’s company cafeteria.

A WasteNot! WantNot! LLC placard hammered into the wall reads Food In The Home Is Unsanitary! but they’re careful and haven’t been caught.

They sit at the table by the window that overlooks the flooded city. An osprey glides overhead, although she can’t imagine it will have good hunting here. A sheen of oil turns the water mirrorlike beneath the rising sun. Dead trees stick up as posts, remainders of a park where she took Eddy to play as a child. Leon leafs through a decades-old science book whose still-bright photos depict stars and supernovae remnants, gas clouds and galaxies. Tai studies a bedraggled old pamphlet on hacking telecommunications systems he borrowed from Sawyer, using a contraband pencil stub to make notes in the margins.

The fan clicks off as electricity is shut down for the day in all housing units. The warning siren blares. As they hurry down the echoing, concrete stairs, the boys tell her about a girl who was expelled from school yesterday because the family couldn’t pay her fees.

“What happened then?” Rose asks.

Tai shoots her a warning look. “She’s my age,” he says, which means he doesn’t want to say any more in front of Leon.

“Ah. You mean that pretty girl, Becka.”

Tai blushes. “That’s not what I meant,” he grouses.

“I know it isn’t,” she says gently. “I’m worried too. She’s a sweet girl. She brings her malnourished little sister into the clinic every week for her vitamin shot.”

“I saw her parents outside,” says Leon unexpectedly. He’s a sharply observant boy, wise beyond his years. “They said she wasn’t fifteen yet. Too early to start her service. The sentinels arrested them for causing a disturbance. Amma, they weren’t even shouting. Just asking for a recalibration on the fees. She was supposed to have earned extra because she tutors younger kids in math. They said she was given no extra credits for the work she did.”

Tai breaks in. “The company never gave her the high score bonus she was due. She scored top of the school in math and engineering proficiency.”

He closes his mouth as they reach the bottom of the stairs, where they might be overheard. It’s not flood season, so the rooms on the ground floor of this former office complex have been set up as a dormitory for one of this year’s two cohorts of debt laborers. It’s best never to be heard criticizing the company. People get extra credit for reporting malingerers and malcontents. But the ground floor lies empty. The “summer sparrows” have already left to buy a meal from Healthy Kitchen! LLC before the time clock shifts from “prep period” to “task period.”

Outside, Rose and the boys each click over five credits to step up onto the raised boardwalk owned by Secure Walking! LLC. The rent they pay to Hope Housing! LLC is low here on the flooding verge, but it’s against the law to use the old non-fee roads and sidewalks, which have been condemned and placed off-limits even though they’re no worse than the poorly maintained and cheaply constructed boardwalk. Freedom isn’t free! proclaims a sign on the boardwalk as they walk into the center of town, carefully stepping over warped boards and patches of dry rot. Eddy used to do maintenance on his day off, on his own time. There’s been no one to take his place.

They check in at the Pure for You! LLC vending machines to fill their old stainless steel bottles with the daily water ration and accept their Complimentary! LLC cigarette, courtesy of the company. The line moves quickly, after which they join the queue at Healthy Kitchen! LLC for the mandated daily weigh-in. A dispenser spills out grimy tokens in an amount equal to their allowed calorie allotment based on their weight plus credit rating, which they can trade in at the cafeteria or one of the two automat annexes.

Inside the big cafeteria, the boys pick out their favorites: bread with spread, kelp pudding, protein sausage, and hash browns. They’ll get a protein smoothie for lunch at school. Rose prefers oatmeal with whatever seeds, nuts, and dried fruit are on hand along with a scoop of protein powder. She hasn’t tasted wheat or butter for years but the bread’s all right, some combination of millet and amaranth, and there’s always plenty of peanut butter. They sit at a table to eat.

Over the years locals have decorated the cafeteria wall with a bright mural depicting the town and its environs: the drowned city with ghost outlines of its old contours, half-sunken boats covered in barnacles, owls skimming over the oily waters, raccoons scavenging out beyond the fence, cheerful mice and responsible rats busy at work although, if you understand what to look for, the decorative flower wreaths are really chains sealing doors and windows. Crows circle overhead, spying on everything. In the distance, tucked into a tree-lined valley beyond shadowy hills, a dappled cow with a distended udder grazes peaceably and a watchful hawk soars in the distance, barely more than a sketch of outstretched wings.

Rose knows everyone, and greets people as they arrive and leave. Tai whispers intently with a pair of friends who made fifteen a few months ago and were sent to apprenticeship positions in the salvage yards, roaches in the ruins, as this new generation call themselves.But all too soon they have to bus their dishes and head out as the time clock ticks inexorably down toward “task period.”

She checks the boys in at the school and, after they’ve gone in, pauses in the entry foyer with its racks for coats and shelves for outdoor shoes. Through an open door she watches all ages of children sit at tables facing a big screen; there is no image playing, just a blank, black void. The screen is where Best Outcomes! LLC pipes in classes from an inland enclave where company citizens live. That the screen is dark now is unusual since in the morning it always plays a recorded ball game from one of the enclaves’ professional sports leagues, sponsored by Your Entertainment! LLC.

Many children slump with bored faces, but a small group has clustered around Tai’s chair as he explains something in a low voice. His passionate expression worries her, although she would never ask him to change. He is his father’s son, angry and determined to make whatever small changes are within his power.

Uncle Cristiano, the school’s custodian, makes his laborious way up to her. The foyer is a good place to talk as it lacks a surveillance camera.

“The feed cut out twice yesterday, but it was running fine when I put it on sleep mode just before curfew,” he tells Rose in a voice softened by early-stage mesothelioma. He ought to be retired and resting, but to receive the minimal treatments available he has to be employed.

“Sure does seem glitches and cuts happen more often these days,” she agrees. “It wouldn’t be so bad if they’d adjust the fees when it happens. Or offer an alternate curriculum. Books, maybe.”

He wheezes a sarcastic laugh. The school removed the library of print books six years ago and now requires the students to pay per page viewed on tablets they can only access at school. “Central office didn’t credit any of the children the last set of their community maintenance work hours and in-class shared tutoring. You heard about Becka?”

“I did. What do you think?”

He frowns. “Nothing good. We have to hope her engineering potential will spare her the worst. The thing is, Doc, I’m not sure the screen shutdown this morning comes from the company’s end. It costs them nothing to run the old AI teaching program. That thing was out of date thirty years ago. You hear anything about a gunshot just before dawn?”

“I heard it. CM-70”

Abruptly he coughs, hand pressed to chest and bending forward with a spasm. A proximity alert shivers in her combat link, the triple buzz signaling an unknown who is potentially hostile. Before she can step forward to see if Uncle Christiano is all right, his gaze flashes up to meet hers, then flickers past her with a warning look. Belatedly, she hears the tromp of confident footsteps. Definitely hostile. She sets fists on hips, arms akimbo, to block the view into the schoolroom.

The children have already heard. Inside the classroom, they scatter to their assigned seats. Tai slips something into a pocket.

A sentinel unit stamps in through the entry: tall, well-fed young men from the hill enclaves. They patrol the town in threes, wearing the gold badges of Safe For You! LLC pinned to the glossy black uniforms that give them the nickname of crows. They carry the dual-shot carbines like they are third appendages.

“How d’you do, Doc?” they say with big, bullying smiles as they sweep past and take a turn through the classroom, ogling the older youth in a grotesque way that makes her think of pretty Becka. All the students stiffen, keeping their gazes safely lowered.

“Hey! Uncle Crusty!” The sentinels beckon to the custodian, who shuffles toward them as they laugh at his crooked gait. “Why’s your screen down? You get a fine for turning the equipment off!”

“I didn’t turn it off, sirs. Our screen was down when I got in this morning. I sent one of the students to the supervisor’s office to report the shutdown. Must have come from the company side. No fine, in that case.”

“You township lowlifes are all lazy liars,” scoffs the corporal, who looks maybe nineteen, cocky with power. “And you, old man, you’re just a waste of air. Can’t even work a decent day’s labor, can you?”

Tension scalds the air. The children don’t like the old man being mocked, but they keep their mouths shut and heads down. Tai gives a flick of his hand to send Rose off. He’s growing up. Taking responsibility. So like his dad and mom.

Her tracker buzzes as the time clock siren wails a last long blare signaling the end of the morning “prep period.” She’s late. She takes the hint from Tai and heads out.

Fortunately, the clinic is only a block away, on the corner of the central plaza, next to the barber shop and public baths. All three are owned by the health branch of Best Outcomes! LLC.

Winnie, the clinic’s clerk, sleeps in the clinic, which allows her to unlock the doors at the first tracker buzz. It also allows Winnie to take twilight raccoon deliveries of off-market herbs and bits and bobs of outer-reaches salvage that the clinic uses to supplement the meager supplies and equipment the company provides. Rose hands her complimentary cigarette to Winnie, who will use them for barter. Even if Rose wishes people did not smoke, she understands why and how the company works to make it happen. They encourage people to go further into debt however they can.

The waiting room is already full, people seated on hard benches. A thin child coughs exhaustedly, slumped against an elderly woman, Arlene, who is draped in a threadbare shawl. With a palsied hand, Arlene is signing a promissory note for treatment for her sick grandchild. Arlene herself has a treatable condition, but from the beginning the company dealt harshly with any persons who had worked in the legal professions. Once a paralegal at a firm specializing in consumer protection lawsuits, she had been assigned to clean toilets and to muck out the filtering grids and drainage pits in the salvage yard. When she could no longer manage the punishing physical labor, the company refused to transfer her to a desk job. So now she can only get medical care for her grandchildren, who have future worth for the company.

As Rose adjusts a medical grade mask over her face, Arlene says, “Those crows sure made a ruckus early.”

“So they did. Woke me up.” They exchange a nod.

A baseball game plays on the big screen, Wings versus Hammers, the volume turned down to background chatter. “Fly ball to right field…and…Smith catches the ball at the warning track!”

Rose walks on through the waiting room. There’s another mural here, a sequence of old-fashioned farm scenes: a red barn with sparrows roosting along its roof ridge, a henhouse with smug hens overseeing fluffy chicks, a green tractor with a calm cat at the controls, a herd of cows with calves grazing in a wide open pasture, mice and rats seated at a table in the hayloft sharing cheese, monstrous mosquitos and ticks with stolen plates being marched off in disgrace by officious dogs, a gate in the shadows half open to reveal a bounteous garden beyond.

She nods at people she knows, and notes individuals she’s never seen before, twice as many as yesterday, most coughing or wan with fever: a virus has hit the dormitories, brought in by the most recently arrived summer sparrows.

Clarissa, the clinic intern, moves through the room taking histories, triaging the patients, and handing out reused masks to people who don’t have one even though Best Outcomes! LLC policy states that it provides masks free of charge to prevent epidemic disease outbreaks, according to the terms of the armistice.

Clarry is a bright, eager sixteen-year-old with what Rose judges is an authentic calling toward healing. She can’t afford the next level of schooling, only available in the inland enclaves. The company has allowed the girl a waiver to work as an unpaid intern at the clinic rather than sending her to the yards or one of the raking crews. Rose can’t pay her either. Knowledge is the only currency she has after forty years as a medic turned nurse. The town will need someone to look after people when she’s too infirm to work since the town isn’t on the list to receive a nurse after she’s gone.

Winnie points with her right elbow toward the back. Clarry looks up, giving a sharp dip of the chin. Urgent.

Rose goes into the back, past the exam room and the sterile procedure room to the storeroom with its half-empty shelves and a surveillance camera that’s been hacked by Sawyer with a staggered loop for the last eight years. In the shadowed back, on a scrupulously sterilized foldout metal table, lies a young woman curled into a ball, arms clenched over her abdomen, moaning with a quiet, hopeless keen. There’s blood on her skirt and no one with her.

Rose comprehends the situation at once. She doesn’t recognize the young woman, who wears a debt laborer’s uniform, always a skirt and blouse for women. She’s a new seasonal from the cohort housed on the other side of town, closer to the salvage yards.

“I’m Rose.” She wants to rest a reassuring hand on the patient’s shoulder but they’ve never spoken, so she needs to wait and establish trust.

“Doc Rose,” whispers the young woman, repeating a name someone has told her.

This isn’t the time to share that she’s a nurse, that the town hasn’t had a doctor in twenty-four years, only a screen that connects to Your Friendly Doctor Art Gence! LLC. “What’s your name?”

“Gloria.” After a pause, she adds in a frightened whisper, “I don’t want to die.”

“Gloria, you’re losing blood. To figure out a treatment I need to know what method you used.” She doesn’t say “abortion” out loud. Even with the hacked surveillance camera it’s too risky.

“I didn’t! I’m not! They’ll arrest me.”

“Help me help you, Gloria. Once you’re stabilized—” She doesn’t say if. She needs her patient to believe in her. “—is there a safe place you can rest for a few days?”

“I got no free days to cash in.” The young woman catches in a sob. “Anyways, there’s nowhere safe, is there? They…they came into the dormitory.”

Rose’s heart hardens as she sets her rage and fear aside and closes it off so she can work effectively. “Here’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to diagnose you with respiratory syncytial virus. A fresh variant is going around right now. I’ll tuck in someone else’s positive results to your paperwork. That means I can assign you a place in the isolation hall. It’s over behind the bathhouse. There’s a twenty-four-hour sentry on duty to make sure no one leaves so sickness doesn’t spread.”

“Sentry? A sentinel?” The girl shudders, arms folding tight over her breasts. There’s a rip in her blouse’s collar.

“Sorry. It’s not a company sentinel. I say sentry but I mean the janitor for the bathhouse. He lives there, always on duty. He was a marine in the war, a long time ago now. No one gets past Sawyer if he doesn’t want them to. That means no crow can get to you there.”

“Crow?”

“It’s what we call the sentinels.”

Gloria shrugs, shaking her head because she doesn’t understand.

Rose can talk to her about the local code later. “Since I sent two sick folks over yesterday, you going there today won’t light any alarms. Four days’ quarantine is what I can give you. Then you have to return to work”

“But what about food? I don’t got an allowance or any extra. What about the toilet cost? Won’t it report the blood? They track our periods.”

“I understand your concerns. Let me reassure you. Quarantine has a separate set of regulations because the company wants to avoid an epidemic. You get two meals a day brought to your door. As for the other, there are no toilets in the quarantine building. You get a toilet bucket with an odor lid. There’s a separate waste sterilization vat for quarantine. It won’t be analyzed except for disease. You’ll be isolated, no one to see you or talk to you. Can you manage that, Gloria?”

The young woman releases a pain-filled sigh. She begins to talk in a low, frantic tone about the assault that happened ten weeks ago. She was one of two women who arrived three days ahead of the other seasonals because of a schedule glitch in the cargo trucks that haul the cohorts. The sentinels who came into the dormitory wouldn’t take no for an answer because why should they? The company owns her like it owns this town.

“Who was the other woman?” Rose asks with sudden dread.

“Oh, they didn’t touch her. She has that skin thing. Lizard scale. Afterward, she was crying and let me sleep with her in her bunk. I felt safe there. That’s where I’ve been sleeping, between her and the wall. She told me not to say anything. If they find out you been raped, then they fine you for being a sex worker. I’d get moved to Funnel Point. No one wants to go there. It’s a slaughterhouse. She said it would be okay, there will be fresh fish soon, but who eats fish? They’re all poison.”

Fresh fish soon. Is the other woman an informer from the central office hoping to find out whether the township had been infiltrated by outreach from the Neutral Zone? Direct outreach is illegal according to the terms of the armistice. Or maybe the other woman is just a regular sparrow who keeps her eyes and ears open and learns from the people around her?

“What happened to her? Is she still around?”

“Yeah. She works out at Rock Wall with a freight unit. She’s the one told me to find Doc Rose. She asked at Rock Wall. Said she wanted to know who the local doc was because of her skin condition. No one traced the question to me.”

“I see. Does she have a name?”

“She goes by Lizzie. Like lizard scale, don’t you think?”

“Could be.” Although in the bedtime stories told to the children, a “lizzie” is a splendid magical creature who grants wishes. Rose sets the thought aside and gets back to business. “Now listen, Gloria, this matters a lot. You’re bleeding. I need to know how you did it. That’s the only way I can help you.”

The young woman wipes her eyes, convulsing at a fresh wave of pain. “Snakeroot. Picked it myself, up past the fence. There was a place where the chain-link was cut and you could peel it back. That’s how I got through. In the transit dormitories, they say snakeroot works.”

“All right. It does work, but not in a safe way. It’s dangerous for multiple reasons. Here’s what I’m going to do, Gloria. I’m going to insert seaweed into your cervix to dilate it, get it to open. Then I will do a procedure called a D & C that will basically clean out your uterus. I need to do the procedure to make sure you don’t get an infection in there. Dilation will take until tomorrow. I’ll send you over to the bathhouse while you wait. You will feel a lot of discomfort as the seaweed expands. You must stay quiet. Can you do that? Good girl. Buckle up.”

Rose works in silence as Gloria alternates between holding her breath with stubborn courage and sniffling out weak sobs. The military inserts prove useful in procedures since she can use them to zoom in for a high-resolution look at injuries, and to measure tissue for elevated temperatures that might signal a local infection. After the seaweed is in place, Rose gives Gloria a second pan of sterile water to clean herself up as well as a clean skirt and underpants with several changes of reusable sanitary pads and a pail to soak them in.

She walks Gloria out the back into the courtyard with its covered cistern shared between the clinic and the public baths. A proximity shiver on her link warns her that Sawyer is moving her way. A moment later, he opens the locked back door of the baths and wheels out to see why she’s come. He’s a stocky man about her age, tough and sarcastic, with a sharp tongue and both legs lost above the knee during the war. He assesses the situation with a glance and gently takes the girl under his wing. Maybe it’s the squeaky old wheelchair that comforts Gloria or maybe just something about Sawyer’s twinkling eyes and compassionate gaze.

The rest of the day passes quickly, one patient after the next with the usual complaints: three skin infections, two infected abrasions, a rush at lunch break of patients coming in for their daily pain meds—since the company requires each dose to be dispensed in person to prevent drug sales or barter on the gray market—and this season’s spike of viral respiratory disease. She sends two more people to the bathhouse’s isolation hall. If more show up, she’ll have to double up rooms or ask for a dispensation to establish a quarantine zone in one of the dormitories.

It’s a long day, with one short break for a lunch of protein sausage, bread with spread, and maize porridge, but it’s always a long day. A few people leave modest gifts of food or produce or random items on a little alcove shelf tucked out of the way in the foyer behind the coat closet, a place not visible to sentinels should they barge in. At five o’clock, the tracker buzzes to announce final shift, the long three hours from five to eight. There’s a twelve-minute transition with ten minutes of calisthenics and stretching and a two-minute gratitude meditation that is a recording sponsored by Healthy Outcomes! LLC.

About an hour later the boys come in together, having completed their after-school community chores. Tai hangs up his jacket and goes over to the bathhouse where the time clock will show him as assisting Sawyer with janitorial duties for further work credits. In reality he and the wily old marine will be working on something they hope will bring down the blackout through explosive sabotage, a last-ditch option Sawyer is skeptical about but Tai insists has to be considered should no fish be caught.

Winnie and Clarry juggle a late rush of patients who take advantage of final shift’s lower penalties for taking time off. Clarry has gotten very good at delivering vitamin shots for young children with as little discomfort and fear as possible. Leon cleans the clinic, his work so efficient that he can sneak five minutes here and there to continue studying an anatomy book whose yellowing transparencies reveal how the structures in the human body are layered together.

At seven, the tracker buzzes to signal “cool down.” The last rush eases as people head home before curfew. While Leon and Clarry and Winnie close up, Rose goes through the back to the bathhouse.

Gloria’s gritted jaw suggests she is in pain from the seaweed, but she doesn’t complain.

“I’ll do the procedure tomorrow,” says Rose. “Be patient. Be a barnacle.”

“What’s a barnacle?”

“A creature that holds on over the years, even in erosive settings.”

“Oh. Okay. The soup is good here. Better than we get in the dormitory.”

“Make sure to tell Sawyer. He likes a good compliment. It isn’t easy to cook tasty soup with what we have to work with. But we’ve learned.”

“Do you have to go?” Gloria clutches her hand as if it is a lifeline. Rose’s years as a medic and town nurse have taught her that, in truth, she bridges the gap between death and life. It’s a big responsibility, but then again, the town functions not because of the supervisor seated in his air-conditioned office with twenty-four-hour-a-day electricity and access to the company’s up-to-date technology, but because each individual even at the lowliest job has a part to play in the community’s constant struggle to survive.

“I do have to go, love, but I’ll be back in the morning. We’ll get this sorted out. You’ll be all right.”

Gloria wipes away a tear. “How can I be all right? They’ll do it again. Who’s to stop them? Lizzie said rape used to be a crime, a long time ago. Is that really true?”

“Would you like to live in a place where the company wasn’t in charge?”

“There is no place like that.”

“What if there was? What if you could call out so someone in that place heard you? And what if once they heard you, then the company would have to let you go and live there?”

“Oh come on, Doc. That’s just a stupid story people tell, about a cow that gives milk from its breasts…no, they call it something else.”

“Udder.”

“Yeah. But no one even has cows except rich people in the enclaves. There is nowhere else. Just more of this.”

Rose’s anger swells to become something stronger, a righteous rage that this young woman has no hope for anything better, no belief there could be a future beyond the regimented life of debt labor to the company. To those who grew up inside the company, there is no other world they know, and thus no pathway except to more of the same. But Rose and LaChelle and Sawyer and Arlene and a few others are old enough to remember the armistice and its legal fine print. Arlene had long since memorized the salient clauses and wrote them down in secret.

Epidemics need to be protected against since they cross borders. No dumping waste in river or sea water, which crosses borders. Air quality controls, since the wind blows pollution where it wills. People have the right to ask for severance, to leave and go elsewhere, even into the Neutral Zone, as long as their debt gets paid.

Section 3. Right to Leave and to Seek Asylum. No State, no corporate entity exercising the powers of a State, and no officer or agent of the same shall abridge the right of any person to depart the jurisdiction thereof and to petition the Neutral Zone for asylum. Every person so petitioning shall be received by the Neutral Zone as an asylee, save upon a specific finding by a court of competent jurisdiction that such person poses a clear and present danger to the physical safety of the inhabitants of the Neutral Zone. This right of egress and asylum shall not be suspended or denied on account of distance, the passage of time, any declaration of emergency, or any other pretext whatsoever.

The old civil government hadn’t quite lost the war, but it hadn’t quite won either. An armistice with concessions agreed to on all sides was the most any could manage. Being stuck on the wrong side of the armistice line hadn’t seemed so bad, not at first. Not until the company had shut down all communications and even the supposedly unassailable combat comms links.

Sawyer has a tiny secret office tucked out of sight past a tool closet behind the cistern. He’s back there with two of the owls, supervising Tai as the boy removes their trackers. Rose figured out a physical workaround some years ago: For trusted volunteers, she extracted the tracker and inserted it into a tiny ceramic cylinder that is securely taped into their armpit, easy to miss unless the supervisor mandates a strip search of all yard workers. The tiny cylinders will go to the boarding house to make it look as if Shorty and Paulina are asleep in their bunks. The salvagers will go out on the water, unable to be tracked.

“Are you the ones who were out last night?” Rose asks.

“No, Doc,” says Shorty. “That was Joey and Handsome. Didn’t they come by?”

“I saw them at dawn.” She adds anxiously, “Any chance they got caught?”

Paulina shakes her head. “We’d’ve heard if there was a ruckus.”

“What was crow bait last night?”

“Odds on it being a flying fish from outside. We heard a rumor at Rock Wall that someone saw a white tanglefish in the water by Lao Point. It was broken and only half submerged, so they threw rocks at it until it sank. We’re going tonight to fetch it, if we can.”

“Take care.”

The night salvagers leave for their boarding house, where they’ll nap until the last siren at midnight and then head out.

“What do you think about the squawk we heard? Besides it being a CM-70, I mean,” Rose asks Sawyer as the boys shoulder their packs for the walk home.

“Hard to say. Let’s see if Shorty and Paulina find anything. Could’ve been debris.”

“What if nothing ever changes?” Leon asks, not angry, just resigned.

“Then we keep working,” says Sawyer.

“I’d rather just blow it all up!” snaps Tai, clenching his hands, breathing hard.

Rose rests a hand on his arm. He never grew taller than her. All of the children born here are shorter than their parents, shorter even than Shorty. “Day’s not over yet. Let’s go before we get a curfew fine.”

The boys understand their grandmother can’t afford a fine, so they hustle up. After clicking over the required credits, they head back along the boardwalk on the familiar route. The proximity link shivers in three short bursts.

Ahead, three large figures loom out of the late twilight gloom. Their swagger makes Leon shrink back and Tai puff up angrily. Rose doesn’t falter. She walks right up to the one in the lead and halts, keeping her body between them and her grandsons.

Sentinels are required to keep guns and uniforms in best order. One of the guns is so new the sentinel hasn’t yet peeled its label off the shoulder-stock: Carbine, Multipurpose, Model 70, featuring an advanced gas regulator detection system to switch between lethal and less-than-lethal rounds without any additional adjustments. For the discerning peacekeeper. Caution: using multiple types of rounds in the same magazine not recommended.

“How can I help you?” she asks. “We’re on our way home.”

The sentinels laugh coarsely. “Looks like we got us a tiny troop of lazy liars. Why you out so late…”

The corporal gestures for the sneering speaker to stop. “Doc Rose? That you?”

“It is,” she says cautiously. It’s never good to be stopped by the sentinels, especially at night, next door to curfew.

“Good thing!” says the corporal. “We got a medical question.”

“Your unit has a medic,” she says evenly.

“Yeah but we get a demerit if we come down sick. Frankie here got scratched by that little hellcat. It was just a scratch so we didn’t think anything of it. But it got all red and nasty. Show her, Frankie.”

Frankie winces as he unbuttons his uniform shirt and peels it back to show lurid, puffy red lines across his shoulder. It’s infected.

Rose has a lifetime of experience controlling her expression. A white-hot burning part of her soul wants to tell him to rub salt in the wound, but she doesn’t. Becoming a barnacle when the toxic waves roll through is the hardest part of the work.

“You’ve got a skin infection. I don’t have any antibiotics—”

“How can you not have antibiotics?” the corporal scoffs. “The salvage rats get cuts all the time.”

“And die of them,” she snaps.

Taken aback by her harsh tone, they shift away from her, hands restless on their carbines. The tracker buzzes, two short, one long: fifteen minutes to curfew. She has a long-practiced medic’s tone for fraught situations.

“Corporal, I recommend you buy honey from the garden market and smear it on the infection. It’s a natural antibiotic and might help. If it doesn’t, you’re going to have to go to your medical unit, demerit or no demerit. An infection like this can spread to the blood, if it hasn’t already.”

“But—!”

“You can come see me tomorrow at lunch, if you must. I’ll clean out the wound, see if there’s anything else I can do with what I have. But I strongly recommend you take the demerit and see your medic. If that is a highly resistant staph infection, you don’t want to be on the other end of what it will turn into, if it isn’t already too late.”

She wants to say more, much much more, like it would serve him right, but she doesn’t. She grabs Tai’s elbow and steers him past the men, Leon right at her heels. The sentinels let them go as they start arguing with each other about whether to report to medical or not.

She and the boys hurry home.

The electricity comes on at eight, rationed through an elaborate system she doesn’t understand, something the company has plenty of resources to implement. They have two hours of electric light, after which only the fan will run, and that only because fans help keep mildew at bay. The mandate changed ten summers ago after a rash of heat-related deaths, after which Arlene staged a sit-down protest on the former supervisor’s doorstep and reminded him of the company’s legal obligations respecting basic human care.

Leon finishes the book on the universe and asks Rose for permission to read her hefty Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, the one she keeps hidden in their room because it would be confiscated if anyone saw it at the clinic.

“It’s pretty heavy going,” she says.

He gives her a wildly expressive eye roll, and she gives him a hug, which he shrugs off with a blend of annoyed independence and little-boy affection. Then he opens the book and is lost to the world.

Tai tells her he’s headed down to the far end of the building to hang out with a schoolmate until ten, and goes out.

Rose tucks a pair of carrots and a gnarled potato into her shirt, making it pouch forward as if she is a prosperous person with plenty to eat and a proud belly to show for it. She climbs to the roof. LaChelle sits at an old café table on a spindly chair. Her seamed face is illuminated by low red light arising from an old night-fighting technology implanted in officers’ hands.

There’s no camera up here, no one at all. The laborers aren’t allowed, and not many locals live out so close to the shore. Rose sits down opposite LaChelle and pushes over the produce, which the colonel tucks into a pocket. She sets an object on the table. Her faintly glowing hand reveals it as a sleek silvery cylinder no longer than a small thumb.

Rose stares in awe, touching it as if it is a holy relic, forbidden. Of course, such a glittering little minnow is indeed forbidden. “I heard there was some tanglefish debris out by Lao Point. Shorty and Paulina are going to fish it out tonight, if they can. What is this?”

“When you said where you saw the rowboat, I searched where the currents would pull wreckage. It took me all day because the wind patterns are shifting, but I know this shoreline.”

“None better,” agrees Rose.

“I found this washed up on Maizy’s Beach in a sealed pouch, wrapped in seaweed for disguise. This is it, Rose. The fish that’s not been poisoned.”

They sit for a while in silence overlooking the drowned city. A searchlight sweeps the water beyond the sentinel tower, where the company’s pier juts out with its official salvage boats tied up in a line, ready for tomorrow’s work. Lights give sparkle to the town. Rose can’t quite hear people talking in their homes, but she feels them: the coughing child, the traumatized young woman, the elders keeping the old knowledge alive and the youth seeking to learn and create new patterns, the night salvagers whispering to each other as they decide what course they’ll take across the water, the laborers settling to sleep as they brace for another day of exhausting work.

A shadow appears at the stairwell’s entrance. Tai slides noiselessly over as he sometimes does. He’s got an instinct, that boy. He sits in the third chair. LaChelle gestures. Carefully, trepidatiously, he picks up the cylinder and examines it from all angles. His grin is something to see, more brilliant than a thousand stars.

“I’ll plug it in just before second buzzer. I think that will work?”

“We can but try,” says LaChelle. “You know the tech better than I do. But most of us know the drill, should we succeed.”

The final warning buzzes. Lights out in fifteen minutes. Rose and Tai go downstairs. He clutches the cylinder as if he is never going to let it go. When they reach the room, he whispers a few choice words to his little brother, whose eyes widen although he says nothing. Rose isn’t sure how well the boys sleep that night, but she sleeps well, because back in the day she learned to sleep wherever, whenever, and she’s never lost the habit.

No shot wakes her. Birdsong wakes her, the old soundtrack from a lost world where wings trace vast pathways across the land, able to migrate where they will.

The boys are silent this morning, nervous, determined. They click over the credits for the boardwalk, make their way into town. Arriving early at the school, Tai gives her an entirely unexpected hug before he hurries in. She needs to check on Gloria, so it’s with some concern that she sees Winnie standing at the clinic door facing a tall young woman whose face and hands are speckled and gleaming with the silvery condition known as “lizard scale.”

The woman steps right up to Rose, towering over her. “You’re Doc Rose, aren’t you?”

“Yes. You must be Lizzie. Gloria told me—”

“No. Listen.”

“Not out here.”

Rose takes her into the back, into the storage room with its looped camera. “You aren’t here to check on Gloria?”

“No. I mean, yes. Of course. God, what a nightmare. That poor girl. She’s only fourteen, did you know that? I wanted to kill them. But hold on, hold on. Not now.” With a deep sigh, and a sharp exhalation, she controls herself. “I heard a rumor from that hot sexy gal Joey that the old colonel found the breaker.”

“The breaker?”

“Do you have it?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Lizzie grits her teeth impatiently. “If you do, and you’re going to try it, it won’t work without this.”

She holds out a black pin that’s about an inch in length. “There’s an insertion point in the cylinder. You put it in, then plug the cylinder into any of the company screens. They all have a scrambler and a control node. This will break through the company lockdown. But you won’t have much time. They’ll reboot and scramble within sixty seconds.”

She might be a company informer. Yet her easy and casual reference to Joey as a hot sexy gal suggests she might be the real deal. Under company rule no one would dare say that aloud about a person of the same gender. Lizzie seems oblivious, as if she’s from a place where no one cares, the way it was when Rose was a young woman. During the war, Rose survived more than once because she went with her gut feeling.

“All right,” says Rose. “I’ll take it where it needs to go. We know what to do.”

“Do you?”

Rose says nothing, just looks at her with weary eyes.

Lizzie has the grace to look abashed. “They told me not to underestimate you all.”

Rose snorts. Lizzie hands over the pin, so slender and seemingly frail. Rose closes her fingers over it. “Best you get on, Lizzie. If this works, you’ll see.”

She heads toward the front, then feels a proximity shiver: hostile. From the clinic waiting room, the corporal’s voice raises, loud and insistent. He’s asking for her on an urgent matter. She dodges out the back, past the cistern and into the bathhouse. Sawyer looks up from the front desk. She gestures a “cover me” as the footsteps and voices of the sentinels come closer; they’re searching for her in the back courtyard. He nods. She ducks out through the barber shop and its alley back door, jogs as best she can on her arthritic knees to the alley entrance to the school where trash is set out. She knocks with the SOS rap on the storeroom door.

Leon opens the door. “Amma! What are you doing here?”

Eight minutes to the second buzzer.

She slips inside, into the storeroom where Leon has been reading a print book away from the eye of the classroom camera. “Get your brother.”

He gives her a startled glance because of the sharpness of her tone but understands that her clipped voice means “emergency.” After grabbing a broom and dustpan for disguise, he hurries back through an interior door into the classroom. A minute later Tai returns with the broom and dustpan, which he sets down before he takes the pin. He understands the object immediately in the same way she understands a medical condition she’s studied and treated.

“Oh, of course,” he breathes. “I get it. That’s really clever. I need to connect them before the daily feed turns on.”

Six minutes to the buzzer.

Her hands and feet turn ice cold. She can’t catch her breath.

He’s already gone back into the classroom. She shakes herself free of paralysis. It takes her two minutes to reach the clinic. She shoves the door open with so much strength it bangs against the wall. The people waiting on the benches jump nervously, look up, see her, and relax.

From the desk Winnie says, “You all right, Rose?”

Rose looks at the screen. The Wings player wearing jersey 19 has just hit a single and halted at first base when the image flashes white, obliterating the game. A garbled voice emerges from the light, cuts out on a crackle of static that resolves into a tone so high-pitched that everyone winces, followed by silence. The bright screen darkens, like shadows emerging to swallow what can’t be seen. A face comes into focus. No: two faces, staring in wonder and concern out at people they cannot see. They wear their hair oddly, one with his head wrapped in a colorful scarf and the other with her scalp shaved down as if for a medical procedure. From what Rose can see of their clothing, they aren’t wearing company-mandated uniforms or any of the seasonal clothing offered for rent at the company store in limited styles and colors.

Standing at the door into the back corridor, Clarry blurts out, “Those are outsiders. Like you said there were, Doc. I didn’t believe anyone really lived beyond the enclaves.”

Winnie calls out, to the screen, breathless, as frantic as someone gulping in a last gasp of air before their head goes under water. “Can you hear us? By the rights accorded all civilians and former soldiers in the armistice, we request asylum. We desire to move territory.”

A murmur runs through the waiting room. Rose raises a hand for silence. “They can’t hear us. They can only hear where it’s connected.”

The door from the back slams open. The sentinels barge in. Everyone hunkers down, trying to look small.

“Where’s that coming from, Doc?” demands the corporal.

She shakes her head. “I can’t hear anything,” she says, since it’s better to speak truth when you don’t want to reveal what you know.

The two people on the screen are nodding, listening. After a bit they speak, as if in reply. Tai knows the necessary phrases. So does Leon, Uncle Cristiano, and a few of the other students whose families have clung to the struggle all these years and never given up on the idea that each node and each pathway and each fresh connection can in time spark with life.

The screen snaps to black with a final pop. The clinic lights go out. Someone has cut the power. The sentinels scramble outside. Winnie opens the shutters of the window behind her desk.

“Do we go outside?” she says to Rose. Her voice trembles.

“We go outside. They heard us. They’ll come.”

Will they, truly? She doesn’t know, but she does know that, for this one moment, they have touched the greater community, the wider world, beyond the wall the company built.

She opens the door and goes out, scanning for the sentinels, but they’re running toward the tower where they can find out what’s going on. Sawyer wheels out of the bathhouse, tipping her a nod. Gloria walks gingerly behind him, holding tightly to the wheelchair’s push handles.

Others emerge mouselike onto the streets from the small factory shops where they do company work: five, ten, twenty in a group. Rose walks out onto the plaza, to the plinth where once a statue of a man holding a rolled up piece of paper stood, although the statue has long since been taken down. Uncle Christiano leads the children out of the school, walking in neat lines with young children paired with older ones. After fifteen minutes, more than two hundred people have assembled in silence in the plaza.

From up here she sees a flood of workers leaving the salvage yards, headed their way. Not everyone will come. They just need enough to stand strong together, to wait for an hour or more. She knows the borders; she knows how fast helicopters flew, back when she was in the military, but there’s surely something newer, faster, more fuel efficient.

Sentinels appear up on the tower. There is a water gun on the tower alongside two machine guns. Will they panic and fire? Or will the supervisor tell them to stand down? How long can anyone endure this tension without breaking? No one is meant to be out and about on company time. Everyone here is breaking company law by walking off their jobs. But the salvage workers march closer, singing a song about roaches. The sentinels don’t shoot.

Arlene pushes through the crowd, leaning on a cane and carrying a burnished leather briefcase. “I’ve got my copy of the armistice in here,” she says.

Leon breaks free from the line of students and comes over.

“Where’s Tai?” Rose asks him.

“He stayed in case the connection comes through again. He’ll hide if he hears anyone.”

The crowd grows. The minutes pass, one after one after one. Ten. Twenty. An eternity.

A small electric cart races into the plaza, scattering people. The supervisor gets out beside the plinth. His assistants unfold a portable stairway for him to climb up to the top. Once up in this commanding position, he raises a bullhorn.

“This is an unlawful assembly. As a courtesy, and pursuant to clause three point two point nine in your contracts, I am giving you one warning to disperse. After that, you will force me to take drastic action.”

Rose waves to get his attention, then steps forward to speak in a loud voice that carries across the crowd.

“Supervisor, we have the right according to the armistice to request transfer into the Neutral Zone, which we have done. Let any others raise their hand to show they request transfer.”

Leon raises his hand. Arlene. Winnie. Clarry. Sawyer. LaChelle, still puffing from her long walk up from the shoreline. Cristiano. The children. The barber. The salvage workers as they crowd in, old rats and young roaches with their hands to the sky. The people, those who have come out onto the street based on what has been passed mouth to mouth, ear to ear, over the years. Many have come. Even wan Gloria raises her hand, although she seems unsure what is going on.

The supervisor’s grimace is fierce with anger and a touch of panic. He shouts into the bullhorn. “This is your final warning!”

No one lowers their hand. They stand there, united in a purpose so many have worked on together for so long to bring about.

Leon tilts his head. “You hear that?”

She looks up. Everyone looks up.

A light flashes in the distance. She uses her inserts to zoom in, but she doesn’t recognize the vessel, and it’s not yet close enough for her proximity link to register its presence. Sawyer has the same inserts. He looks at her, his grin like lightning.

“Not a company vessel,” he shouts.

The supervisor lowers his bullhorn and stares at the sky. The wind rising off the water rumbles. A seagull glides past, headed for the sea. An old promise grows in the distance, coming their way. The sun gleams across the waiting multitude.

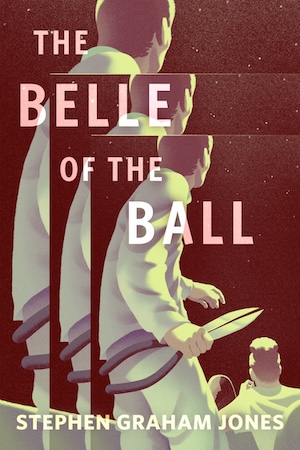

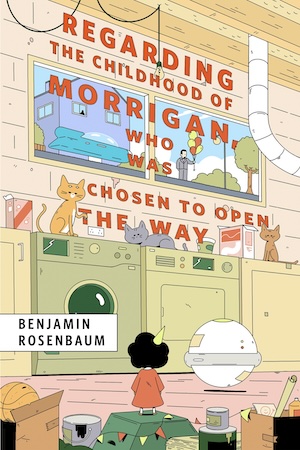

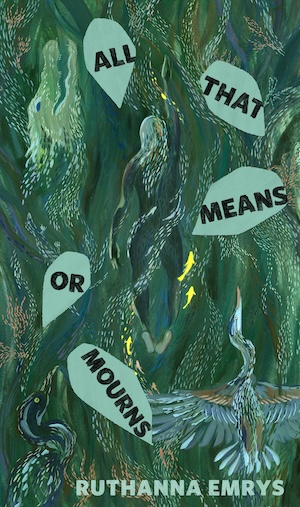

Author’s note: I wrote a very early and much shorter exploration of this story concept in 2019 because I’d been thinking a lot about a road trip conversation with my beloved dad back in 2000 in which he asked, “What would a pay-as-you-go society look like?” (he was not a fan of the concept). A chance to expand on the ideas and plot came during the 2023 Vaster Than Empires writers’ workshop sponsored by the Berggruen Institute. The help of everyone at the workshop in refining these ideas is gratefully acknowledged. Special thanks to Ken Liu for answering an in-story legal query with his usual aplomb. Many thanks to Oliver Dougherty for editorial guidance and keen line editing, and to the Reactor Magazine team for their usual excellence.

“Barnacle” copyright © 2025 by Katrina Elliott

Art copyright © 2025 by Juan Bernabeu

Buy the Book

Barnacle

A sharp jolt of hope, fought-for, endured-towards. What a timely release, what a brilliant read.

oh, this is lovely. thank you kate elliott, we need all the hopepunk we can get right now.

Rereading this, I was struck by the little detail of somebody who grew up in the city before it was flooded not having a name for the statue of the man “with a rolled-up piece of paper in his hand.” My first thought was Christopher Columbus because killdeers are American birds and the names of the characters appear to be North American. Imagine being North American and not knowing who Columbus was. Imagine how much history you would have to not know, not to have a clue–as a grown adult–who Columbus was. What a deft way to show the depth of the failure of the former state.

So inspired by the environmental and social commentary that sparkles as narrative on the page.

The family relationships between Rose, Leon, and Tai are so touching and grounded, especially enjoyed and got a big flash of understanding at Tai waving Rose away when the sentinals show up to bully at the school.

I’m haunted by the details of the complementary cigarettes and mandatory 2-min gratitude meditation. Gloria’s story was a powerful inclusion as well.

Love the themes of non-violent resistance and knowledge as power.

Thank you for sharing this story!

Just finished the first draft of my second novel. It’s a different take than yours, a more hopeful take, on the post-apocalypse. The effects of end stage Capitalism plays a big part in my story. Slavery plays a big part. Your story, Kate, is more than dystopian. It is the hell that is being suffered right now by people all over the world. We might not have it as bad in the US, but in my neighborhood, poverty and wage slavery is the lot of so many people. When I started reading, Barnacle, I thought, “Oh, just another of those stories that are so popular in SF now.” But you caught me and drew me in. You did it with sharp characterization and hope. These stories are popular now because we SF writers see the future. We write stories of hope out of desperation and because rebellions are built on hope. Thank you for this.

This is so powerful, it feels so real. I was repeatedly on the verge of tears reading it. It captures so well my fear of where we are, where we are going, and the power of every small act communities do to help each other survive, despite the hostility of the capitalist system we live in.