Transformed by a broad-spread fungal infection that connects humans with nature, one woman feels closer to the world than ever, but further from the people she loves the most…

Short story | 3,565 words

In the foyer, I shed the hospice’s cleansuit. The medically-licensed plastic sticks to my skin; the vent draft chills where I peel it away. I want to tear it off in handfuls. But I pull slowly, excruciatingly aware of every blocked pore, and finally stow it in the UV box contaminated but whole. Another visitor will need it soon, to dull their senses and reassure the dying.

Outside, Florida’s humidity is a living slap. I’m drenched in sweat despite my neck fan. My eyes sting; gut microbes churn with anticipatory grief. At least I’m no longer isolated. Sporulated whispers surround me. Even the parking lot holds life: gnats and tenacious anoles, bacteria in the soil beneath the permeable pavement, cracks pressed wide by choirs of lichen. My mycelial network yearns toward its kin, but the Animalia Serenitas Center would not approve if I sank to their killed-myco brick graytop to meditate.

The rental car automatically unplugs as I approach. No trains or tramlines here, in the sinking lands stolen from the Everglades. The driving assistant has regressed to default settings, and I have to readjust it—again—to my rare driver reflexes. I try to appreciate the trivial distraction, but it only feeds my pain. Mom’s dying grows tendrils into everything.

I need my fellow hyphae. At home I would bike to the cranberry bog or the maple swamp or the dunes, immerse myself in friends and neighbors. But Naples is an antifungal enclave where most people only step outside in sterile cleansuits. Corkscrew Sanctuary is the nearest option. The winding boardwalks, the miles of mangrove and cypress and sawgrass, the alligators and herons let everything in.

At the entrance, a screen lists birds sighted this week. When I was little, the board would be full by Friday, notes crowding into the margins. It’s sparser now. Watchers still spot the white ibis, the great blue heron, the peregrine, and the bald eagle, but the wood storks have been gone since the second-to-last avian flu, and other species have fallen to heat or storms. Or salt water, rising through porous ground to claim the grassy river. The swamp lets everything in.

The sun beats onto the tall grass and I’m forced to open my parasol, blocking the cloudless blue-gray sky. But there’s relief in the shade of the cypress trees. Even the mosquitos, fellow psilocordyceps hosts, take only a token blood offering. Their sting’s been bred out; I offer them a taste of megafaunal complexity and receive in turn an instant of blur-fast wings, ganglial hunger, and the purity of their swift satiation.

The boardwalk winds through shingled bark and cypress knees, slow water thick with fallen leaves, the sudden chitter of a cormorant, baby alligators sunning on logs. No turtles for years now. Mom loved this place, used to take hours identifying species while I raced impatiently ahead. Even before the cancer, she lost that; the hike was too hard in a cleansuit.

I don’t see any other humans until I reach the hyphae nest. We’ve taken over one of the old pit-stop gazebos, added hammocks and live-myco cushions to make comfortable laybacks, wound vines and branches through to ease connection. Two people sprawl with closed eyes and peaceful smiles; one is up and stretching. She bends her knee and lunges, back leg taut.

“Welcome!” she calls, unworried about waking the others. It’s just another greeting, natural as the cormorant’s. I fall into her offered hug, already sobbing.

Her body is more familiar than mosquito or moss, easy to interpret. Heartbeats and lungs sync up. Nerves fire like city lights. Her digestive system’s busier than mine. Fibroids snake through her uterus and something’s off in her lower back, a practiced drone of pain. Nothing unusual in her brain. I pay attention to brains, lately.

“My mother has glioblastoma,” I tell her. “She’s antifungal; I can’t make it feel real. I’m not ready.”

She holds me tighter. “I came out here with my brother every week while his lungs were breaking down. We could share everything. It’s never enough.” She leads me to a hammock, wraps me in vines. I close my eyes.

Mycelia transmit more slowly than neurons, and over longer distances. The world enters in patches. Strangler figs drink in sun and water and carbon dioxide, basking and growing and sending out lazy chemical signals. They drape over ink-scratch branches of cypress and curl against ragged bark. Branches stretch up from the trunk, trunks from knees that drink deep of the shallow water. Mushrooms grow into the roots, digest fallen logs, extend microscopic tendrils through mud and heron. The swamp flows slowly, shaped by every tree and fish and leaf and pebble, feasting on rot and breathing out abundance. I stretch my senses, loving and becoming.

As the whole rich system fills in, so do the lesions: acidity that singes gills, salinity that leaves larvae scrawny and weak, hungers where no hunger should last. Flickers of incomprehension, wordless mourning for prey long gone. Through it all winds the same psilocordyceps that inhabits me, that grows through almost everything now. Infection, bond, witness.

The human brain can only imagine itself a swamp for so long, even with practice. We have always been torn between wholeness and the quick, anxious passions that separate us. My hearing is first to retreat into my body: The other hyphae are awake and arguing.

“It has to have been deliberate. Random mutation would give you itchier athlete’s foot, not make you one with the universe.”

“I’m not saying it was random mutation. I’m saying the release was accidental. Someone meant to use it in a lab, for medical imaging or surveillance or some shit. If there was meaning in it getting out, it wasn’t human.”

“Are you talking about divine intervention?” This voice belongs to the woman who welcomed me. “Or are you saying the mushroom escaped on purpose?”

It’s a familiar discussion, endlessly interesting to some, endlessly dull to others. I go back and forth. Should it matter if the greatest gift of the twenty-first century was truly a gift? Nothing, god or human, has ever demanded our gratitude. But we would have questions, if we knew some cause beyond chance, and perhaps the unwanted offering of our gratitude anyway. Why not be grateful? Few things are better than they used to be.

“Purpose is a human thing,” says the second voice. When I open my eyes, the two earlier sleepers are sprawled together on the bench, one nested in the other’s arms. In the mycelial network they feel like a single organism, skin comforting skin.

“Purpose is a human illusion,” I offer, letting the conversation draw me into a different sort of connection. “We’re not as good at choosing actions, and their consequences, as we like to think.”

“So accidents are a human thing, too. Everything else just is.”

The argument continues: The question of how we, who now share senses with all of nature, can claim that nothing else has goals or choices or screwups. The question of whether there’s some higher purpose to those screwups, whether we’re ants unaware of the anthill. The question of what sort of purpose would allow the sheer levels of screwup that humans have managed.

This connection I can hold even less easily than the swamp: I let it fade again into a background drift of primate calls. The idea of purpose, and the thought that there is none, are both too painful. We can’t be all that means things, or all that mourns. There are flocks of feral macaws in the trees. We can’t translate them, but surely like us they circle the same questions over and over.

Like us, wherever they came from originally, they’re bound now to something dying.

I spend the next morning sorting papers at the house. Staying there means I don’t have to worry about hotel quarantine policies, but it also surrounds me with work of dubious utility and endless urgency. Dad had just moved into the antifungal apartments, and Mom was trying to sort everything out so she could sell the place and join him, when she got sick. Everything is half started or half done.

I might be able to sell the house to an antifungal, but not for much. Everyone knows Miami is in its last years. Salt infests groundwater and eats holes in the land above, and soon the antifungals will find another place where sinking land is cheap. I could abandon the place. After she dies. When she can’t know that I gave up on what she left behind. Or I could talk to her friends who side-eye me for being hyphae, ask them for help finding someone who needs the space and can take over the mortgage, someone who will glare at me for the gift.

So many places are salvageable, even on the coasts. Places where the bedrock is less porous, where long years of local organization and semifunctional state governments have funded seawalls, pumps, purification plants. There the hyphae do more than witness: We diagnose and treat and help the world adapt, find points where the right push can save a sliver of world.

I picked up signals once from a frog that we’d thought extinct. I recorded their calls and the pattern of their heartbeats, shared my data with other searchers, and we found enough to bring a breeding population together. We worked with the psilocordyceps to protect them from simpler and more deadly fungal infections. There’s a type of frog now in northern Maine that wouldn’t be there if I hadn’t paid attention and chosen to do something about what I found.

There’s nothing I can do for Mom. There’s nothing I can do for the Everglades. My love is useless here.

In the hospice cafeteria I sit with Dad. I can’t eat through the cleansuit and would quail at food I couldn’t sense—even aside from the fungicides, there might be anything in it. I haven’t shared a meal with my parents for two years.

I would’ve said we were close. We called every week, told each other about concerts and meals and broken appliances and broken weather, about birds spotted and books read and friends visited.

The question, unasked for two years, sits in the back of my throat.

He prods at his sandwich: fresh-baked sourdough piled with eggplant and roasted tomato. He takes a slow, forced bite. His eyes are distant. It would be cruel to ask him, now, why they pulled away from the world they taught me to love.

I remember the debate in the hyphae nest, the pain of unanswerable questions eased by shared sensation. I touch Dad’s arm with my suited hand, knowing he’ll flinch, offering and taking comfort anyway. At least he doesn’t pull away, just lets his head fall with the weight of everything we’re carrying.

“The nurse says it could be any day now,” he says finally. “But it could be a week or more. She’s got a strong heart.”

“She was always about . . .” I wave my hand vaguely, indicating years of hikes and high-fiber foods. “Do you remember the carob chip cookies?”

“Unfortunately. And that one stand at the farmers market that I swear put dirt in their muffins.”

“God, she loved that place, I have no idea why. She thinks they’re delicious.” I hesitate over tenses. She’s not quite past, not yet, but she’ll never again buy a dozen gravelly muffins for a potluck. Or else she is past, only her unconscious body withholding permission to acknowledge the loss. But the talking, at least—about her, not about us—creates some sort of backup, an echo of herness in our shared memories. “I wish healthy food were as nice as healthy exercise—she could always find the best walks.”

And Dad lifts his head, a fraction, and talks about the research she did when I was a baby, ten different apps to find one that could consistently recommend stroller-friendly hikes, and the places they got stuck, laughing and lifting, when the first tries failed.

In the corner beside the spare room couch I find the archaeology of Mom’s knitting: half-finished hats with crumpled patterns on top, simple pairs of slippers in all her family’s sizes, then the little spring-green afghan that I snuggled when I was five, and finally the lowest layer revealing some forgotten decade of leisure: an exuberance of lace shawls dewed with sparkling beads.

It should be the hats that hurt most, with their evidence that her organized mind was breaking down before anyone noticed, pushing against the start of the project again and again, as if this time she would find her way past the barrier. When I came to visit two months ago she was doing that with simple things: shuffling her feet forward and back, forward and back, lifting her walker and putting it down, explaining to us that “I just need to . . . first . . .” before trailing off.

Or it should be the afghan that makes me cry with safe-childhood nostalgia, as though childhood ever feels safe to anyone but grown-ups. Maybe the shawls should make me pine for the selfhoods she set aside in the press of work and childrearing. But it’s the slippers, of which I have a dozen pairs at home in Massachusetts, one from each Chanukah since my feet reached their adult size minus those worn out by late-night fridge raids. No one will ever take care of me in that precise way again, and I’m not ready. I curl over the pile, burying my tear-streaked face in yarn. Sometimes it comes like an avalanche: no one to sing “Old Devil Moon” as an off-key lullaby, no one extolling a specific breed of yeast over the rhythm of homemade bread dough, no emailed list of local trails every time she knows I’m traveling. And someday—it feels as real now as losing Mom—someday Dad will die and I’ll lose his ability to identify even the rarest out-of-place birds, his perfect foraged salads, his ability to turn everyday frustrations into giggle-worthy gossip.

And no matter how many hard conversations I try to have or avoid, there will be things I regret never asking and things I regret saying at all.

I sleep with the afghan that night. It’s not safe, but it’s simple. My mycelia reach out through the fabric, along the bed and the walls, looking for something to touch. They find a spider weaving above a dusty shelf, and my dreams are full of vibrating silk and mosquitos winking out like candle stubs.

The hospice calls at four am: any minute now. I struggle awake with cold tea and pull the car jerkily out of the driveway before I remember again to reset it. Breathe in the calm of sleeping birds in the parking lot, gulp morning mist, take too long to get the cleansuit on with shaking hands. What if I’ve missed it?

Dad is by the bed; I join him in the comfortable chairs. Mom’s favorite klezmer plays quietly from hidden speakers, anomalously cheerful. Her breathing is abrupt: inhaling into a frightening gurgle, snorting out, long pause, repeat. Every pause might be the one. We sit watching, waiting.

“Do you want some time alone with her?” asks Dad. “I’ve already said everything I need to.” I nod, and then it’s just me.

“Why won’t you let me be with you?” I whisper. But hearing is the last thing to go, and asking her is even crueler than asking Dad. “I love you. I have a good life, I’m doing good work. I’ll be okay, and I’ll keep going, and I’ll remember you every time I go for a hike.” I go on like that, saying the little reassuring things that I guess I’d want to know, if I were dying and had a grown child. I feel bad, because I do want kids and I don’t have them yet, and they’ll never get to meet her. I don’t say that, and I don’t thank her for not nudging me about grandchildren. Nothing aloud, except for the things I can promise will continue past her horizon.

I run out of things to say, and she’s still breathing: gurgle, snort, pause, repeat. Time feels impossible: We’ll be in this limbo of waiting forever. Dad isn’t back. I could slip off part of my suit, brush her face, let the hyphae give us a last moment of connection. Isolated in her body, maybe she would appreciate it now.

I hover. But it’s a childish urge: to do the forbidden thing, to get castigated with crumbs still on your tongue. The remnants of Mom’s choices depend on our cooperation. Then there would be Dad’s choices lost, and the other patients’ and their families’; my hand drops, clenched with responsible misery.

Dad returns. “The nurse says that sometimes people wait until they’re alone. That they don’t want their family to see.”

“I guess that makes sense.” It makes sense as something they tell you to give meaning to the meaningless, or to help you feel okay about not being in the room, waiting forever. Somehow, someone who hasn’t been able to move her foot consistently for two months will claim this last bit of control over her movement from being to not-being.

It’s dusk when I return to Corkscrew: almost cool, almost comfortable. Sawgrass chirrs. A heron rasps, and an owl sends up its banshee cry from amid the mangroves. I stretch for memories of what it sounded like when I was younger, here with Mom and Dad: What’s been lost? I must have neglected so many details.

I hoped for human company, but the hyphae nest is empty. The park closes in half an hour. In Massachusetts it wouldn’t matter: There would be as many witnesses to the nocturnal ecology as to the daylit one, defenders and scholars of peep frogs. Maybe the disapproving neighbors discourage it, or maybe no one wants to sit vigil in the dark, waiting for salt water to slowly drown the fresh. Loons call, and early nightbirds, and I hear the low rumble of an alligator chiding her babies.

We never know, for all that we share our senses, what else in this world feels grief.

I lie there for a long time, trying to lose myself in awareness of other creatures. The precipice will come soon, and I’m not ready. I can’t get away from telling myself stories about how I’ll feel tomorrow. The opposite of anticipation: Now my phone will vibrate, and I’ll know. It’ll happen now. Now. Now.

I imagine talking with my mother, something I haven’t been able to do for four months. Why come here? Why did you choose to separate us this way? But no, if I had one more chance to talk with her, I’d pick another conversation. Something trivial, gentle. I’m thinking about getting a new cat. A tabby, like the one we had when I was little.

But then, that circles back to the same thing. The relationship I would have with a cat now is different from toddling after shape and fur, never understanding the fear that leads to a scratch or the way a purr feels from inside. Those things I couldn’t talk about, or must, would form a barrier either way.

At first it was common: So many people who weren’t infected immediately found ways to hold it off. We’d rather wait, they said. We want to know more about what we’re getting into. See if there are any long-term effects. Then the hyphae didn’t get sick, and we saved frogs and put intimate sensations into scientific papers. People got curious, or comfortable, or bored, or just tired of barriers. The holdouts grew fewer.

Why you?

Steps echo, hollow percussion on the boardwalk. I lift my head even as I realize that this isn’t the company I sought, let alone imagined. The cleansuit outlines a blank space in the world.

The swamp is all shadows now, glints of salmon and indigo through the trees. It takes me a minute to recognize Dad: his stride slowed by hesitation, squinting even now to track one of the bird calls, familiar striped shirt compressed under the suit. Mom always rolled her eyes at those shirts, but he bought them five at a time. Hard enough to find one thing that fits, he’d said.

“What are you doing here?” slips out, rude and foolish. But I didn’t tell him where I’d be. It’s been years since we walked here together. My stomach drops, and my voice. “Is she—?”

He shakes his head. “I guessed you’d be here. It’s where—” He waves at the nest. “I guessed.” He sits on one of the laybacks, awkwardly, brushing aside dangling leaves. This place isn’t made for avoiding touch.

I’ll only have so many conversations with him; that feels real now in a way it never did until this year. This one isn’t the last. But it’s the one for today, the one we’ll remember having in the suspended hour before Mom is gone and only matter remains. Here on my side of the thinnest barrier, alone with a dying world, I try to decide what to say.

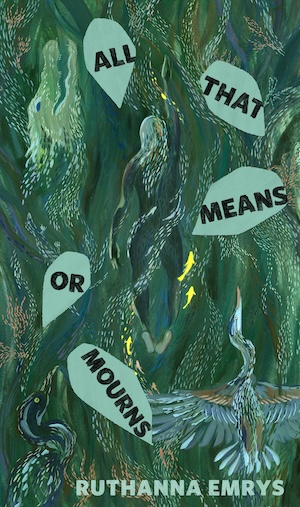

“All that Means or Mourns” copyright © 2025 by Ruthanna Emrys

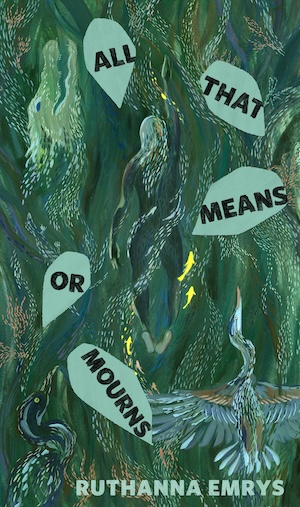

Art copyright © 2025 by Jacqueline Tam

Buy the Book

All That Means or Mourns