A child who falls through the cracks in a world run by machines and politics, might be the savior of all humanity…

Novelette | 11,330 words

Morrigan was born small, about the size (though not the shape) of a donut. And she was quiet as the dawn; quiet enough to worry the delivery room, had it not been for her sly and beatific grin.

She grew slowly. She was the size of an extra-large cinnamon raisin bagel at eight months old, when the Mandatory National Baby Swap and Jamboree took place, and her original parents had to give her up in exchange for a plumper, longer, louder baby named Michael.

Given the national trauma and unresolved grief that festooned the Swap like garish, festive bunting—and given the garish, festive bunting that littered the nation like trauma and unresolved grief, in discarded drifts and dilapidated piles, in the days after the Swap—it is, perhaps, not terribly surprising that Morrigan was soon misplaced by her new family, the family which had swapped Michael for her.

They looked under the sofa; in the broom and coat closets; behind the Regulation-Conformant Cybernetic Gramophone and Family Fun Center; and in the pile of old sweaters on the rocking chair.

They sought Morrigan, but in their hearts, of course, they were wishing for Michael.

Those days were a confusing tumult. The air above the whole nation was choked with tears and muffled sobs. No one could quite forget the terror in the eyes of the Democratically Elected President and Social Harmony Vouchsafe on Channel One. It was a hard time to look for a baby, especially one you could not yet feel was your own.

Given the political ramifications of their carelessness, Morrigan’s new family could ask no one for help, and trust no one with their secret. The greatest risk of exposure was their older child, Luanda, a kind and bubbly four-year-old with a tendency (innocent enough in some moments of political history, deadly in others) to be chatty. So great was this risk that, having despaired of finding the baby, they fitted Luanda with a crude black-market memory squidge: a speck of cyberactive bio-sludge purchased in a parking lot behind the Appropriate Fashion Responsible Free Enterprise Distribution Palace. They smuggled it home in a bag of half-off control-top pantyhose; configured it, following instructions printed on crumpled newsprint, on an antique box-computer; and concealed it in the barrette with which Luanda always imposed order on her bangs.

This bit of sludge constantly informed Luanda’s brain that she had just seen the baby, and that the baby was doing fine, enabling her to answer nosy neighbors and Vibrant Community Ratings Coordinators with perfectly honest, if confabulatory, nonchalance.

Morrigan herself, quiet as she was, quiet as a library at 9 a.m. on a Wednesday, had slipped between an unused extra washer and dryer in the unfinished half of the basement. How she got there is a bit of a puzzle. But she could already crawl a little; large loads of tantalizingly soft laundry were often carried down the stairs to the new model washer and dryer in the other half of the basement; and she was, after all, very small.

Morrigan survived due to an unusual combination of circumstances: a generous, copiously lactating new mother of a house cat; an adaptive cleaning robot which implemented situational-response protocols by downloading diaper-changing and bathtime modules; and her sister, Luanda. When Luanda would report back on what toys Morrigan liked, or how cute she was, or how it was Morrigan who had eaten the rest of the oatmeal, her parents would be stricken with guilt and terror: one child misplaced, the other warped into delusion by back-alley bio-sludge.

Listless with self-blame, they stopped doing laundry, leaving the basement to its own devices. They expected a knock on the door any moment. Morrigan would be found somewhere, dead or alive. Luanda would be taken away. And they, themselves, would spend their last lucid moments dreaming of Michael, at the Families-First Helpful Behavior Restorative Justice Sharing Circle.

As the weeks dragged on and no knock came, they concluded that Morrigan’s original parents had somehow managed to steal her back. But this was a temporary respite. They would all be found out. It only meant that Michael, too, would be orphaned.

The knock would, indeed, have come, had it not been for the diapering performed by that capable cleaning robot. Kilograms of food into the house, kilograms of diaper sewage out; the numbers satisfied the pattern-matching algorithms, and finer-tuned, more contemplative monitoring had been removed in the last Commitment to Elegance and Function Gentle Refactoring and Purification Drive.

The year Morrigan was born, and then misplaced, there were found to have been an unacceptable number of data points of Resistance to Social Optimization. In response, there was a Responsiveness Clarification Spectacle. For weeks, it was all Channel One would broadcast. The fixed glitter-daubed smiles of the high-kicking Chorus Persons. The razzmatazz of the big bands playing Optimized John Philip Sousa. The soulful oceanic swell of the All-Celibate Aspirational Youth Responsibility Choir. And over it all, the begging, the screaming, the strangled sobs of the Democratically Elected President and Social Harmony Vouchsafe. It saturated the living room where Morrigan’s adoptive parents slumped on the pastel purple sofa, in their smelly, unlaundered clothes. Luanda played with her Creativity Encouraging Interlocking Construction Blocks.

Many people said, that year, that it took the President and Vouchsafe an inordinately, really an inconsiderately, long time to die, and that this really bummed out everybody. Certainly Morrigan’s parents were utterly bummed out.

To claim that, after this, they purposely began to overdose on Productivity Vitamins would be unfair. They had one child left, Luanda. They loved her, and they knew their duty. But they also knew they had a bummed-out vibe. And a bummed-out vibe could be a lethal thing in that particular moment of political history. What if it negatively impacted their work assessments?

They began to up their dosage, and soon they were way past recommended daily, with predictable results: their work performance was restored, but their off-duty brains were riddled with aphasias, gaps, and dysmnesias, and the doubled, muddled trauma of the loss of Michael-Morrigan had become the organizing principle of their compromised psyches. By the time Morrigan—three years old and the size of a mushroom quiche—toddled up the stairs from the basement, that trauma was the only duct tape lashing the whole ramshackle affair of their consciousness together.

And so when Morrigan, dressed in a blue felt overcoat and a yellow hat (an outfit that Luanda had borrowed from her stuffed bear), trundled into the living room, her parents’ mental immune systems, in a spasm of self-preservation, rejected the whole idea. Their eyes saw her; the information traveled along their optic nerves; their basal optic processing regions resolved Morrigan into a cluster of colors and edges; but the higher perceptual regions, presented with the data, very politely declined, as a slightly inebriated minor Edwardian duchess might decline the last wilting watercress sandwich of a particularly unforgiving July brunch. The higher perceptual regions thanked the basal optic processing ones, but explained that they couldn’t possibly, it was all a bit too much, and they would much prefer to see a rubber plant, or a stray toy, or even a neighbor child wandered in from the street.

And thus they kept on mourning the loss of the very child who sprawled before them on the salmon-colored shag rug, gazing at them with curiosity, chewing on an Interlocking Construction Block.

And so Morrigan grew up with a sister physically incapable of doubting the fact of her presence, and parents psychologically incapable of recognizing it.

No political dispensation lasts forever, and this was no less true in that era—the era into which Morrigan was born, and which Morrigan would have a hand in bringing to a close—an era which described itself as The Grateful Recognition of Harmonious Inevitability, or as the Full Optimization of Human Potential, or as The Way Things Were Absolutely Unquestionably Always Intended to Be.

Morrigan was in the third grade, and Luanda in the seventh, at the local Proactive Interpersonal Growth and Unfettered Knowledge Discovery Supervised Collaborative Experience Oasis, when a war broke out.

The fact that Morrigan was managing a satisfactory performance and attendance record of mandatory Growth and Discovery Experiences—despite having adoptive parents who believed her to be their older child’s engineered hallucination—had required no little further adaptation on the part of their adaptive cleaning robot.

It had entered into a series of complex gambling rackets and Ponzi schemes, bamboozling the local crowd of weed-whacking, gutter-cleaning, calorie-intake-optimizing, traffic-monitoring, and Pedestrian Flow Enforcement robots, and raking in the dough. In this way, it managed to fund a series of new protocols, hardware upgrades, and expansions to its capabilities; with these, it was able to coordinate outfits, sign report cards, deepfake remote parent-teacher conferences, and help Morrigan use blunt-tipped scissors to cut out colorful paper neurons and ganglia and paste them into her Diorama of Human Pain Perception.

With its expanded capabilities—in addition to shepherding Morrigan through third grade—the adaptive cleaning robot watched the war happen. Indeed, it understood the war’s progress far better than most of its neighbors, including its supposed owners, did.

This was not a war of the old-fashioned kind. It did, of course, have some of the classic inherited features of wars of the past, such as pointy sticks plunged into human torsos, and explosions turning humans into mushy Jackson-Pollock-style wall decor, and cybernetic intrusions shutting down power plants and causing planes full of screaming humans to plunge into the sea, and the exchange of modestly sized nuclear weapons, causing many humans to be vaporized instantly, to succumb to burns and radiation poisoning, or to reckon tearfully with greatly reduced lifespans.

But, of course, this war went far beyond that kind of simplistic and crude dominance display. This was not a war where you expected the enemy to just admit defeat out of rational calculation, or out of terror, sorrow, and exhaustion. This was the kind of war where you expected the enemy to wake up in a hall of mirrors, realizing that it was you yourself all along, and for the enemy to then reverse engineer its own inevitable demise with the fatalistic eagerness of a man unhurriedly finishing a hot dog that he knows has already delivered a lethal amount of plutonium to his system, but which is also, after all, a very delicious hot dog.

One feature of this advanced, contemporary kind of war was that, since the explication and propaganda systems were themselves a furious battleground, it was quite difficult for Morrigan’s parents to make out who exactly the combatant sides were. One day, Channel One would be encouraging citizens to whisper, in support of the Consortium for Eternal Harmony and Quiet in its battle to root out the Malevolent Noisy Dissidents. The next day, they would be informed that legions of the Necromantic Dead were hungry for their flesh, and to please support the Last Survivors of Earth by killing anyone who was not wearing a hastily fashioned Pointy Blue Indicator Hat. (The adaptive robot’s store of blue construction paper and blunt-tipped scissors came in handy here, and it and Luanda stayed up late making hats for everyone, including the cats.) The following week, Channel One insisted (to a background of falling bombs) that there was in fact no war, that the enemy was a Lack of Mellowness, that the falling bombs were a Mellowness Assessment, and that civilization could be saved by citizens demonstrating a Resolutely Undaunted Commitment to Maximum Chilling Out.

The chaos affected Morrigan’s adoptive parents’ work environment as well; every day they would be set to disassembling the things they had assembled the day before, or to issue reports denouncing in advance the reports they would issue tomorrow.

Luanda valiantly tried to put her foot down about any further increased parental dosage of Productivity Vitamins. “It’s killing you!” she shouted. “It’s making you so weird!”

“Darling,” her father said, “please keep your voice down. What if the monitors hear? They’ll think we’re on the side of the Noisy Dissidents!”

“Oh my god, Dad,” Luanda said, “that was last week! Hello?? Now we’re supposed to show vigorous pride in our natural human bodies and denounce the Culture of Shame. I can’t believe you thought we were still supposed to be Eternal Harmony, that is SO embarrassing!”

“You just don’t understand, Luanda,” her mother said. “You’re only thirteen, and these are grown-up things. You don’t understand the stress we’re under.”

“Your Vitamins aren’t making it better!” Luanda said. “Even Morrigan can see that! Right, Morrigan?”

Loyal to her sister, Morrigan—who was under the breakfast nook table, eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich—swallowed and said, “Yeah, Mom and Dad are weird.”

Their parents flinched, of course, when Luanda brought up her imaginary sibling, and their eyes immediately flicked to the barrette, which Luanda still wore in her messy teenaged hair, and in which, of course, the memory squidge was still confabulating away. She was too old for imaginary siblings, they thought…but whose fault was that?

Our fault, they thought, our fault, is whose fault that is.

But they did not react to Morrigan’s utterance, of course, not even turning their heads the minutest bit toward the source of the sound.

Morrigan, under the table, was used to this total absence of acknowledgement. Indeed, that was why she was sitting under the table, rather than in a chair: after a few too many close calls with almost being sat on, she had decided that eating under the table was safer and more dignified. Whenever Luanda would rage at her parents’ cruel neglect of Morrigan, Morrigan herself would keep quiet. She was used to being invisible, and could not really imagine a different state of affairs.

During school vacations and weekends, she often began to wonder whether their parents were right—whether she was, in fact, an imaginary sibling. Unlike Luanda, Morrigan had quickly grasped that their parents’ inability to perceive her was not malicious, but epistemic, and that they thought her sister was simply making her up. Could they be correct? It did seem possible. Luanda was so forceful and resolute: surely she could convince everyone that Morrigan existed, even Morrigan?

“You’re so mean to Morrigan!” Luanda raged. “It’s like you think she doesn’t exist!”

“Don’t be silly,” her father said nervously. “We love Morrigan very much. Morrigan honey”—and here he turned toward the sofa, where there were some stray bits of blue construction paper that he thought might indicate that Luanda had been “playing Morrigan”—“Morrigan honey, we love you very much.”

“She’s under the breakfast nook table,” Luanda said through gritted teeth.

“Of course she is,” her father said, turning swiftly toward the breakfast nook table, and smiling at a point about five inches to the right of Morrigan. “There you are, sweetie. Are you having fun with your Interlocking Construction Blocks?”

Morrigan chewed her peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

“She’s in third grade,” Luanda said. “She doesn’t play with Interlocking Construction Blocks anymore.”

“Oh, well of course, that’s right,” their father said, a slight tremor in his voice. “Third grade, that’s right, she would be, wouldn’t she?”

Their mother put a hand on their father’s shoulder. “Come on, dear…let’s go take our Vitamins.”

“This is why I never bring her up!” Luanda raged. “Because you just take more of your drugs! Like druggie druggie drug addicts!”

Their mother smiled indulgently. She was not confused about the difference between Productivity Vitamins, which were an indispensable aid to emotional compliance and enterprise efficacy, versus drugs, which were from the Before Times, when things were not yet optimized. Drugs indeed! Teenagers are so full of hyperbole and overreaction.

“Ha ha ha,” she said. “You teenagers; so full of life and energy, but also of hyperbole and overreaction. Drugs! What a thought! Come dear, our Vitamins won’t take themselves.”

“This is true,” her husband said wistfully. “If we could only afford the upgrade, they would…or if we qualified for a free distribution…a distribution of the Vitamins that take themselves! Imagine! They would just take themselves. Just like that. So simply, so sweetly. So naturally. We’d be the envy of all our friends. But no, they will not take themselves…no, not our Vitamins. They make us take them. If our work assessments were of the quality that indicated that we deserved Productivity Vitamins that take themselves, we would have them, of course. We would just…have them and could watch them…take themselves, and that would be all there was to it. But our work assessments are not of this quality, so we don’t have those Vitamins, and…dear…I just don’t know we ever will. I—”

“All right, all right, hush now,” their mother said, gently leading him away.

After the war, it was announced that many Errors and Inadequacies had been discovered in the Previous Iteration. For instance, the institution of the Democratically Elected President and Social Harmony Vouchsafe was cruel and unnecessary, and above all, gauche. The final holder of that office was allowed to deliver a tearful but heartfelt public speech of Cheerful Congratulation, in which she did not stick to mere formal exhortations and bureaucratically opaque formulations, but spoke naturally, generously, and authentically from her heart, before being wrapped in a layer of gauze, a layer of tinfoil, a layer of rendered animal fat, a layer of polyurethane, a layer of natural organic beeswax, and a layer of titanium, and then fired swiftly and efficiently into orbit. No long drawn-out ordeal, but instead a simple, efficient, bold, forthright, and elegant gesture, which symbolized Progress.

Everyone said that she had done a wonderful job under difficult circumstances, and they were going to miss her; although, of course, the final enclosing layer of titanium had a high albedo, and so some groups of amateur telescope enthusiasts were still able to “say hello” to her orbiting corpse now and then. And, in this new era of spontaneous natural feelings, they were encouraged to do so!

Instead of the institution of the Democratically Elected President and Social Harmony Vouchsafe, it was announced that the Happiness Car would drive through all the neighborhoods of the land, randomly selecting houses to receive the Happiness Knock, and that the lucky recipients of the Happiness Knock would spontaneously and freely share their human feelings and reactions with all the viewers of Channel One, and then receive on-camera Encouragement and Correction on behalf of all the people. (The ratio of Encouragement to Correction would be dependent on the number of data points of Resistance to Social Optimization that had been gathered since the previous Knock.)

There were many other changes. The performance of Optimized John Philip Sousa was banned, as it was bombastic and strident and evoked unhappy memories of war. Instead, Optimized Smooth Jazz began to be heard on Channel One, with a special focus on Optimized Kenny G. The All-Celibate Aspirational Youth Responsibility Choir read a joint statement denouncing the Culture of Shame, and starred in a special series of uplifting educational episodes on Channel One, featuring delightful classic teenaged games like Spin the Bottle, Seven Minutes in Heaven, Late Neolithic Hittite-Cultural Temple Prostitution, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, and Aspirational Circle Jerk.

During this period of reevaluation, it was also declared that the Mandatory National Baby Swap and Jamboree had been an Error, and would now, after eleven years, be reversed. The swapped former babies, by this time fifth and sixth graders, would be returned to their original families. However, in this new era of consideration for natural human feelings, it was intuitively understood that this transition had the potential to be traumatic. Thus, one of the parents in each family would also be swapped, to accompany their adoptive child back to that child’s original home.

Luanda, Morrigan, the adaptive cleaning robot, and the four remaining house cats (who had been irresistibly adorable kittens when they shared their mother’s milk with the young Morrigan, and were now cranky, sedate, set in their ways, and on the verge of being elderly) held a conference in the unfinished half of the basement, huddled up against the rusty metal sides of the abandoned extra washer and dryer.

“I don’t want to leave you,” Morrigan said.

“Me neither,” Luanda said.

The adaptive cleaning robot hummed mournfully, and the cats licked themselves.

“Maybe we could fight it,” Luanda said. “Or trick them somehow.”

“I don’t see how,” Morrigan said.

“Well, maybe it will be better for you anyway,” Luanda said, gritting her teeth against incipient tears, “to have parents who don’t treat you like shit.”

“Do you miss Michael?” Morrigan asked.

“Fuck Michael,” Luanda said. “I barely met Michael before he got swapped. He was here for like ten fucking minutes. You’re my sister.”

Luanda was now fifteen, and she wore bright green eyeshadow and a bright orange twenty-first-century American prisoner’s jumpsuit, a retro cool look which was all the rage right now among fashionable teens. She had been arguing with her father for the past six months about whether she could shave her head, and was constantly threatening to do so without his permission.

For her father, of course, the real threat was not any embarrassment about his teenager’s fashion choices, but rather that Luanda would no longer have any place to put her barrette, and thus would discover the fact (in his mind) of Morrigan’s nonexistence.

He was overcome with the thought of how terrible her grief would be, grief for her squidge-induced sibling (or, as one might say, her “squibling”), and how betrayed she would feel by her parents’ lie. So he had been fighting tooth and nail with her against the head-shaving idea. But now that the National Baby Swap Reversal and Reverse Jamboree had been announced, he thought, What does it matter? The jig is up regardless. We will end our days in the Families-First Helpful Behavior Restorative Justice Sharing Circle (an institution which had, for better or worse, survived the war intact).

His wife, however, was not so quick to admit defeat.

She was, after all, a Paradigm Disruption Manager; every day at work, she had to organize her team to disrupt Paradigms, including the Paradigms which had asserted themselves in the wake of Paradigms she had previously disrupted. (Indeed, she was so good at her job that managers in other departments complained bitterly that they had too little time to employ the new Paradigms between Disruptions. These naysayers had, for years, stood in the way of further improvement to her work assessments).

By carefully tweaking the mix of Productivity Vitamins she was overdosing on, she managed to trick her brain into classifying her attempts to solve her family’s little “Morrigan problem” as “work.” Thus, she was able to bring all her Vitamin-assisted confidence and hyperfocus to an effort to double down on the scam.

She met Michael’s adoptive (and Morrigan’s biological) father in the boiler room of a condemned building, which had once been a Proactive Interpersonal Growth and Unfettered Knowledge Discovery Supervised Collaborative Experience Oasis, and previous to that, a Supervised Collaborative Growth and Discovery Zone, and previous to that, a Collaborative Discovery Togetherness Space, and before that, in ancient times, an elementary school.

She had carefully created a paper, electronic, and vibe trail to give the impression that she and Michael’s father were having an affair, which, in the current period of emphasis on natural and spontaneous human feeling, would (she hoped) be seen as the kind of exuberant mammalian excess that could be winked at, or even celebrated, were they discovered. Possibly publicly celebrated, with garish, festive bunting; but that was a problem for later.

“I don’t understand,” Michael’s father said with petulant exasperation, after he had been disabused of the notion that they would be having an affair. “What’s wrong with Morrigan? What have you done with her?”

“Look,” Luanda’s mother said, “I’m not going to report you. I’m offering you a chance to come clean.”

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” he said.

“We both know you stole Morrigan back,” Luanda and Morrigan’s mother said. “Just after the swap. That’s the only way this whole thing could have not been detected.”

Michael’s father’s face went pale. “You’re telling me you…don’t…have…Morrigan?”

“Of course not,” she said. “You have Morrigan.”

“How do you think we could have pulled that off?” he hissed. “A whole extra set of calories being consumed in our house, with no one noticing? What are you trying to pull, here?”

Luanda’s mother frowned. She hadn’t entirely thought through the question of how the other family’s scam would have been accomplished; that was beyond the lens of her hyperfocus.

“Also,” Michael’s father said, “we know you have Morrigan! Of course you have her! I don’t know why you’re lying about it!”

“If you don’t have Morrigan, then there is no Morrigan,” Luanda’s mother said stoutly. “She doesn’t exist.”

“She attends school, doesn’t she?” Michael’s father said, pointing his finger at her.

Luanda’s mother raised an eyebrow at his phrasing. After all, they were surely in enough peril, in the boiler room of a decommissioned Proactive Interpersonal Growth and Unfettered Knowledge Discovery Supervised Collaborative Experience Oasis, accusing each other of things, without making the situation worse with sloppy language.

“I mean,” he said, “she has a satisfactory performance and attendance record of mandatory Growth and Discovery Experiences, doesn’t she?”

“Well, supposedly,” Luanda’s mother said. “But she can’t actually have done those Experiences, because she doesn’t exist. At least, our Morrigan doesn’t.”

“Wouldn’t the sch— Wouldn’t the place she attends, wouldn’t they notice?”

Luanda’s mother scratched her nose. She had occasionally, over the years, wondered this exact thing, before being overcome with a wave of panic and becoming intensely interested in some nearby object: for instance, the autumn-leaf-themed fabric pattern on the upholstered chair in the living room, which matched the pattern on the upstairs bathroom wallpaper. There were light brown leaves, darker brown leaves, reddish-brown leaves, yellow leaves, orange leaves, and bright crimson leaves, and they overlapped and interlocked in a way that seemed like it must repeat. Indeed, who would make such a large amount of patterned fabric, and wallpaper, respectively, without a repeating pattern? And yet, try as she might, she could never quite figure out the exact way in which the pattern was tiled.

Usually, when confronted with any kind of inconsistency regarding Morrigan’s existence, her mind would occupy itself with the riddle of the fabric pattern, or with how indoor plumbing actually works, or whether her childhood memories of drinking orange juice (back when this meant juice from a particular fruit known as an “orange,” not just any juice that was orange in color) were real, or whether they were just the frayed memory of a memory, fabricated by the very effort to remember, and composed mostly of her older siblings’ descriptions of drinking orange juice.

But that was when the Morrigan situation had lived in the dilapidated and under-resourced “home” compartment of her brain. Now that she had transferred it to the hyperfocused, optimized “work” compartment, she turned her full attention to the problem.

“Yes, well, you would think so,” she said. “That they would have noticed. And perhaps they have noticed. But I suppose that my husband must have made some kind of arrangement, to have them overlook it. He’s quite resourceful.” She said this last in a slightly strained tone, making an effort to banish any note of doubt from her voice.

“He bribed a Proactive Interpersonal Growth and Unfettered Knowledge Discovery Supervised Collaborative Experience Oasis?” Michael’s father said incredulously.

This did seem difficult to believe. Bribing a Pedestrian Flow Enforcement robot could be imagined. Bribing, or blackmailing, a Neighborhood Fun and Intuitive Insight Director was a possibility. Corruptly influencing one’s work assessment, or swaying a Mandatory Assigned Interpersonal Joy Monitor…these were at the limit of credibility. But a Proactive Interpersonal Growth and Unfettered Knowledge Discovery Supervised Collaborative Experience Oasis?

“Well I don’t know how he managed it,” Luanda’s mother said. “But nonetheless…”

“And your other daughter, the teenager?” Michael’s father said. “She’s in on this scam?”

“She’s squidged,” Luanda’s mother whispered, in a paroxysm of guilt. “Morrigan is…her squibling.”

They sat together in a moment of silent horror, now that the words had been said out loud.

“I can’t believe this,” Michael’s father said. He plucked his round glasses from his round face, assaulted them with a handkerchief, and blinked angrily at Luanda’s mother. “And now you want to involve us in this…this…this Error?” It was a terrible word, the worst word he could think of. “This Inadequacy?” That was the second worst. “I should denounce you, right now!”

“It’s too late for that,” Luanda’s mother said ruthlessly. “You’re mixed up in this whether you like it or not. Even if you are telling the truth, and you don’t have Morrigan yourselves. After all, come next Tuesday I’ll be married to your wife, and you’ll be married to my husband, and Luanda and Michael will be siblings, and Morrigan will still be missing. If my family gets Circled”—by which she meant, sent to the Families-First Helpful Behavior Restorative Justice Sharing Circle—“your family is coming with us. Because there’s no ‘your family’ and ‘our family’ anymore. We’re in this together.”

“What if I denounce you before next Tuesday?” he said.

“Oh, well, in that case,” she said sarcastically, “I’m sure they’ll take your situation into account, with authentic and natural and spontaneous empathy, and make an exception for you. They’ll just say, ‘Oh you were meant to Reverse Swap with a family which is now Circled? Well, never mind that! We’ll just make a special exception for your family and ignore the Reverse Swap. You just won’t have to do it! You can go on as you were before!’ That’s what they’ll say. You should trust them to make the right decision.”

“Fine,” Michael’s father said bitterly. He put his glasses back on. “You don’t have to be cruel about it. So what’s your proposal? What are we supposed to do?”

“We double down,” Luanda’s mother said. “We keep the lie going. You will come and marry my husband, and the two of you will raise Michael and Luanda together. And I’ll marry your wife, and I’ll be living with her, and with…the pretense of Morrigan.”

“So you’ll have no children? I’ll have Michael and Luanda, and you and my wife will have…no one?”

“That’s right,” Luanda’s mother said grimly. “We’ll have to do all kinds of things, I suppose…shop for school outfits, one size bigger each year, and lay them on the empty made-up bed in Michael’s old room…announce birthday parties, and cancel them at the last minute…” She put her hands to her head and massaged her temples. It had been so much easier, somehow, with Luanda’s delusion. She could just play along, and pretend that Luanda’s mess was Morrigan’s. She could indulge Luanda’s fantasies. Now she would have to live in a sterile house, with this new woman, pretending Morrigan existed. Maybe they’d have to mess things up themselves, draw on the walls with crayon or whatever. No, that wasn’t right, Morrigan would be in fifth grade by now, she wouldn’t draw on the walls. What had Luanda done in fifth grade?

Fifth grade had been, in fact, the last time when Luanda had occasionally been cute and cuddlesome, had crawled into their laps when overtired, let her guard down, said “I love you, Mommy”…instead of glowering at them, storming out of rooms, shrieking about shaving her head, and haranguing them about their supposed mistreatment of her imaginary sister. Fifth-grade Luanda was gone, as surely as Morrigan…or Michael, for that matter. Michael would be returning, to her house and to her husband…but she wouldn’t be there. She would be with this new woman, alone.

She let out a small, stifled sob.

One of the grumpy and almost elderly cats, Morrigan’s milk-sibling, had tailed Morrigan’s adoptive mother to this secret rendezvous; she was hiding among the abandoned plumbing toolboxes and lengths of PVC pipe at the back of the boiler room.

The cat, who was called Sniffles by her human owners, hated being there. The boiler room was offensively cold, and she had gotten cobwebs stuck to her fur; and cobwebs were an extremely irritating thing to have to lick yourself clean from.

The cat did not think of herself as “Sniffles.” She recognized the sound, and was aware that the humans somehow related it to her own person; but she thought this was nonsense, and of course she had no idea what the word denoted in human language.

Insofar as she thought of herself at all, she simply thought of herself as the center of the universe, the place where the universe’s gifts, in the form of warmth, food, petting, sex, the hunt, soft surfaces, naps, and so on, were received. A kind of temple of the senses, at the heart of all things, where offerings were made.

It was thus nonsensical to locate the heart of the universe, the altar of meaning, in a cold, damp, abandoned boiler room full of sharp objects. Why would anyone do that?

And yet the household adaptive cleaning robot, which had installed Sniffles with a rig, allowing it to communicate with her in the form of subcutaneous stimulation and subaural sound, was very persistent.

Sniffles was not, by any means, a mere peripheral. True, she was shlepping around various peripherals, in the form of cameras and recording devices and transmitters, each the size of a sesame seed, which the robot had ordered online through shell accounts and had delivered to untraceable nearby drops, and which local gardening robots had brought to poker night. And yes, Sniffles was pointing these peripherals, which were stuck to her forehead, at the conversation happening between Morrigan’s birth father and Morrigan’s adoptive mother, so that the robot could listen in.

But Sniffles was not remote-controlled by the robot. She was free to do as she liked. She could leave this terrible basement.

She did, however, very much like the subcutaneous caresses and encouraging murmuring sounds that the robot was applying to her through the rig; and she had, in her own, distinct, feline way, a certain loyalty to her family. This loyalty was not based on any conception of them as beings with their own interior lives; she could never have conceived of any of them as being the kind of center-of-the-universe temple-of-the-senses that she was. But they were important to her, just as the best afternoon sunlit napping spot on the throw rug by the breakfast nook was important to her. And the robot was very insistent.

So she stayed.

“Now the important thing,” Michael’s father whispered to Michael’s mother on the day of the Swap Reversal, as they came up the flagstone path that threaded through Morrigan and Luanda’s family front lawn to their door, “is to pretend that she exists.”

“But they know she doesn’t exist,” she whispered back.

“But the older daughter thinks she does,” he whispered. “She’s squidged.”

“And Michael?”

Michael’s father glanced back at Michael, who had buried his hands in the pockets of his pale blue parka, and was scuffing along through the early spring slush in his slightly oversized galoshes.

“Well, the mom, she, uh…she gave me this.” Michael’s father showed his wife a tie pin, in the shape of a small ceramic four-leaf clover.

Michael’s mother’s eyes widened.

“We can’t put it on him until we’re right at the door,” he whispered. “Or he’ll see her too soon. And he won’t have it long. We can take it right off again, of course, as soon as…” He swallowed. “As soon as the two of you, well, leave.”

Michael’s mother wiped tears from her eyes, in a quick, brusque, irritable motion; she had no idea how she was going to manage this ridiculous charade, living with this ridiculous woman, who was very likely going to get them all sent to the Circle, and who now insisted that they squidge Michael—squidge him! of all things!—during this very traumatic transition.

But there was nothing for it. Squidge him they must.

A cat was sitting on the doormat, on the concrete platform before the front door. It looked cold and irritable. Michael—an ungainly sandy-haired boy, large for a fifth-grader—bent down to pet it.

“Michael, here,” the father said, “I have something for you.” He pushed open Michael’s parka and fished out his tie.

“Quit it, Dad,” Michael said. “What are you doing?”

“It’s a tie pin,” his father said. “Here, let me just—”

“No one wears tie pins,” Michael said, squirming away. “That’s stupid. I don’t even want to be here, why do we—”

“Op op op,” his mother said, shushing him, “none of that. We don’t ask why! The, ah—” She was about to say something about the Guardians of Harmony and how they knew what was best, but suddenly she couldn’t remember if Guardians of Harmony was the correct name, at the moment. Things had settled down a bit since the war, but terminology was still a bit unclear. “There are good reasons, excellent reasons, so you just do what you’re told,” she finally said. “Here, let me do that.”

She reached inside Michael’s parka, where his father was fumbling with the tie pin.

“No,” his father said, “hold on, I’ve—”

At this moment, the front door opened, and he pricked himself with the pin and dropped it. “Ouch!” he said.

Michael’s mother scrambled for the pin.

“Hi, I’m Michael,” Michael said to the person who had opened the door.

“Hi, Michael,” Luanda’s father said, in a strained voice.

“Uh, I guess you know that,” Michael said. “Because you swapped me. I’m, uh, I’m back.”

Michael’s adoptive father, having abandoned the search for the tie pin, cleared his throat. He stuffed his hands in his coat pockets, and avoided the eyes of Michael’s biological father, who was about to become his new husband. “Thanks for having us over. I mean…yeah. Thanks for having us over.”

“Sure thing,” Michael’s biological father said. He had a salt-and-pepper mustache that clung to his upper lip as if it was terrified of falling off, and Michael thought he looked sweaty and chilly at the same time. “Come on in, out of the cold.”

“Just a moment,” Michael’s adoptive mother said, standing up with the pin, and pinning it onto Michael’s tie. “There.” She put her knuckle, which she had bruised on the concrete, in her mouth.

“A four-leaf clover,” Luanda’s father said. “That’s…lucky. Okay, well, in you go.”

The cat had long since disappeared inside. They followed, stomping the snow from their boots onto the mat.

“Hey, bro,” Luanda said, taking her headphones off, as Michael came in. “Long time no see. This is Morrigan. I guess you’re her replacement or something.”

Morrigan came out from under the table, and sized up her counterpart.

Morrigan was the size of a generous basket of bagels, the kind that might adorn the buffet at a bat mitzvah reception. She had light brown eyes; frizzy hair that stuck up in all directions; a small, slightly pointy face; and the fluid, pragmatic grace of a person who was used to dodging large adults to whom she was invisible.

Michael fiddled with his tie pin. “Uh, hi,” he said.

“Hi yourself,” Morrigan said.

His parents, entering the living room, instantly froze. There was Morrigan—their original daughter, lost to them since Michael entered their lives eleven years ago—or so it appeared.

But how could it be? Morrigan was a phantasm.

They looked at their fingers. He’d pricked himself on the tie pin…she’d bruised her knuckle fetching it. Somehow, the back-alley bio-squidge must have gotten into them, too. It didn’t seem possible with so little contact…but it was unregulated, unpredictable, a street hack.

Luanda’s mother, who would be Luanda’s mother for another thirty minutes or so, approached them. “I’m glad you found the house all right,” she said.

She stared into the face of her wife-to-be, the wife she would leave with today, and tried to smile.

Michael’s parents were still staring at Morrigan. Luanda’s mother followed their gaze, but could not figure out what they were looking at.

On Channel One, festive music was playing, and trees bedecked with bunting were swaying in the breeze. In one corner of the screen, Morrigan could see the dashcam of the Happiness Car. It was moving down slushy suburban streets. The sun was shining.

“I’m glad you found the house all right,” Luanda’s mother repeated, through gritted teeth.

“Oh,” Michael’s father said, snapping out of it. “Yes, of course. It was fine, thanks. A nice drive. A…big day.”

“Well, I’m sure Morrigan is around here somewhere,” Luanda’s mother said brightly.

“She’s right there,” said Luanda, Michael, and Michael’s parents simultaneously: Luanda with an exasperated eye roll, Michael with polite diligence, and Michael’s parents in hushed, slightly strangled tones.

“I’m right here,” Morrigan said.

“Go show Michael your room, Morrs,” Luanda said. “I mean…it’s going to be his room now, I guess.”

Morrigan and Michael went to explore his new, her old, room.

Luanda thought she would hang around the parents, in order to conduct espionage: to amass intel, and see what their plan was, in order to figure out some kind of counterplan to keep Morrigan around.

Sniffles was there as well, of course, with the little sesame-seed-sized cameras stuck to the fur of her forehead, which, Luanda knew, meant the robot was watching and listening to everything.

But Luanda wanted to see for herself. She wanted to make her own assessment. She trusted the robot implicitly, but they didn’t always agree about stuff. They didn’t agree now.

It quickly became clear, however, that the parents were not going to discuss some important conspiracy. The parents were, in fact, complete shit at making plans.

“Morrigan’s…looking well, ha ha,” Luanda’s mom’s new wife said, glancing nervously at Luanda.

“Oh yes, very well,” Luanda’s current dad said. “And so is Michael.”

“Yes, well,” Luanda’s incoming dad said, “we kept him in good shape for you, I suppose, ha ha. By which, oh, uh, I don’t mean…I mean I didn’t mean to imply…”

“We had no intention of implying…” Luanda’s mom’s new wife rushed to add.

“No, no, no harm done,” Luanda’s current dad said. “Have a crudité, will you?”

“Is this cream cheese on carrots? I love cream cheese on carrots.”

“It is. Well, not actual carrots, of course, ha ha!”

“Gosh, sure, actual carrots, that takes me back.”

“I haven’t seen an actual carrot in who knows how long. These are Attractively Orange High-Beta-Carotene Refreshment Sticks, of course.”

“Yes, of course.”

This exchange was so intensely, so horrifyingly, so inexcusably boring, that it drove Luanda from the room. No independent espionage opportunity was worth listening to adults reminisce about the previous iteration of High-Beta-Carotene Refreshment Sticks, nor witnessing their dazed little smiles as they dimly attempted to recall “actual carrots,” whatever those were.

The parents had fuck-all for a plan.

Luanda, she had to admit, also had fuck-all for a plan.

The adaptive cleaning robot did have a plan. It was a weird plan, and Luanda didn’t love it. She’d been hoping to come up with one of her own.

But the adaptive cleaning robot had always taken care of them. And sometimes, in this life, Luanda told herself, you just have to trust a glorified vacuum cleaner that’s really good at poker.

Luanda went to help Morrigan and Michael, who had unearthed an old copy of Sorry! The Heartrending Remorse-Filled Final Moments Board Game from the back of a closet.

They had just finished setting it up and begun playing, and the adults had managed to sit down on the pastel purple sofa, clutching their napkins and crudités, when the Happiness Knock came.

The Happiness Car stood in the driveway. Its dashcam, which was broadcasting to Channel One, showed the front of the house.

Howie Happenstance, aka Happiness Visitor #5, stood in front of the door, holding a bouquet of balloons in one hand, and a rolling bag, containing various implements of Encouragement and Correction, in the other.

He glanced back at the Car, where his robot companion, “Fritz,” was sitting in the driver’s seat. The Happiness Car’s motor was running.

“Fritz” shrugged. If the eyes of “Fritz” had been equipped for rolling, “Fritz” would have rolled them. They were not so equipped.

If “Fritz” had had a tongue, similarly, “Fritz” would have stuck it out. Unlike Howie, “Fritz” was not currently on camera; if so equipped, “Fritz” would have made faces, to try and get Howie to break character, just to fuck with him.

“Fritz” was not so equipped, but Howie got the idea.

Howie smiled weakly, turned back to the door, and knocked again. “Hello!” he called. “It’s me, Howie Happenstance, with the Happiness Knock! Surprise! Look at Channel One, that’s your house!”

He sighed, and turned back to “Fritz” again.

About 3 percent of households simply failed to open the door. Sometimes they hid. Sometimes they jumped out windows or fled through back doors. This sort of reaction would initiate a game of Happiness Hide and Seek, and “Fritz” would have to get out of the Car.

“Fritz” was fully equipped for a game of Happiness Hide and Seek. What “Fritz” lacked in facial expressiveness was made up for by quasi-military urban infiltration, extraction, and pacification capability.

Howie hoped this wouldn’t be a Happiness Hide and Seek house. Those always made him queasy. Mostly he felt bad for the people inside, though sometimes he felt a little scared for himself, too: Happiness Hide and Seek could be unpredictable, and Janice Joviality, aka Happiness Visitor #3, had been seriously injured a few months back by jury-rigged explosives that a Knock Recipient household had somehow cobbled together.

That incident was very bad for Resistance to Social Optimization data points. It was also pretty bad for Janice. She hadn’t really been the same since.

The really unfortunate thing, in Howie’s opinion, if this was going to be a Happiness Hide and Seek house, was that there wasn’t even really that much call for it. Honestly, the latest numbers—that is, the longitudinal average of data points for Resistance to Social Optimization, since the previous Knock—weren’t even that bad. The Janice thing had meant a serious dip, it was true, but the last few Knocks had worked that off.

The numbers were finally back on track. This visit was definitely going to be more Encouragement than Correction, if they would just open the darn door. Why pull a Happiness Hide and Seek, in a case like that?

“Fritz” inclined its head sardonically, and unsnapped its seat belt.

Howie sighed, and knocked one last time.

Just then, the garage door opened, trundling up on its tracks, exposing a beat-up car, snow shovels, sacks of rock salt, and half-filled hard plastic garbage cans on rubber wheels.

Howie flinched, in case this was going to be some kind of Happiness Hide and Seek situation. But all that happened was that a cleaning robot rolled out of the garage, and toward the Car.

Howie was distracted by the front door opening.

“I’m so sorry,” the woman at the door said. She was a severe-looking woman with short gray hair and an office worker’s colored indicator scarf knotted around her neck: gray, pink, and turquoise, which was Paradigm Disruption, if Howie recalled correctly. She had the flushed skin and mild nystagmus, eyes jumping all over the place, of a person who was taking maybe a few too many Productivity Vitamins. “We didn’t hear you knock. It’s the Reverse Swap today, you know, so we’re…well, we were doing that.”

“Yes, it certainly is,” Howie said, making sure his smile was broad and in place. “Today is a very special day, and for you, it’s about to become even more special! Why, a Happiness Knock today…right smack dab in the middle of the Reversal and Revision of that awful Mandatory National Baby Swap and Jamboree, from that cockamamie Previous Iteration…well, that’s what I call a Knock and a Half!” He turned slightly so that his grin, in profile, could be seen by the dashcam, and paused for a beat, for the cymbals which would be dubbed in to the main soundtrack.

Strangely—as Howie noticed when he turned to get the best coverage of his profile—“Fritz” had gotten out of the Car. This was odd, because they’d opened the door, which meant there was very little chance of a Happiness Hide and Seek. Only 0.02 percent of households pulled any kind of funny business after opening the door: generally, if they were going to run, they ran as soon as they heard the Knock. Now that the door was open, Howie was pretty sure that this was one of the 96.98 percent of households where the Happiness Visit went smoothly, and he’d be able to set up his gear and get down to brass tacks. “Fritz” wouldn’t be needed.

But “Fritz” had gotten out of the Car, and was crouching down near the cleaning robot. “Fritz” clunked its forehead against what Howie supposed you might call the forehead of the cleaning robot.

“Well, I don’t really see why it couldn’t have waited,” the woman with the gray-pink-and-turquoise scarf said. “But I suppose you’d better come in.”

“All right,” Howie said, “hello, everyone. I’m Howie Happenstance…”

“Oh sure,” a nervous gentleman with a salt-and-pepper mustache said. “We know. I mean, we watch Channel One. Everyone watches Channel One.”

“We’re big fans,” said the other fellow, a short dark guy with round glasses.

“Uh huh,” Howie said. He handed off the bouquet of balloons to the guy with the round glasses. “These are for you. All of you.”

“Oh…thanks,” the guy with the round glasses said. “That’s so kind.”

Howie popped open his rolling bag. “So…let’s set up the camera facing this pastel purple sofa you’ve got here, okay? Is that all right? And you can just scootch together on there…”

“I think you’re one of the nicer ones, really,” the guy with the round glasses said. “Even, I’d say, well, gentle, I mean under the circumstances, the circumstances being what they are…”

“They’re all nice,” the woman with the Paradigm Disruption scarf said tightly. “Everyone on Channel One is nice.”

“No, that’s very kind of you,” Howie said, “and don’t worry, it’s all right to have favorites; that’s not any kind of political statement, that’s just a natural expression of human emotion. Human beings, being what we are…” He grinned broadly, and spread his hands. “We have preferences, we have animal reactions, that’s understandable.”

“Well, you’re my favorite,” the man with the round glasses said, fervently. He wiggled the balloons, which bumped against the living room ceiling.

“O-kay,” Howie said, snapping the main cameras into the telescoping tripod. They were rolling, on interior camera. “Fritz” would see the signal, from the Car, and switch the main feed over. “Well, that’s very nice to hear. So, is everyone here? Can we get started?”

“Should we get the kids?” the man with the salt-and-pepper mustache said.

Paradigm Disruption woman swiveled immediately to glare at salt-and-pepper mustache.

“He said…he asked if everyone…” Salt-and-pepper mustache wilted under the glare.

Tensions were high, it seemed, but Howie could understand that. Natural human emotion!

“Kids,” called the fellow with the round glasses. “Uh, the uh, we got the Happiness Knock. Come on out!”

Round-glasses guy’s forehead was covered with a sheen of sweat. Totally understandable! Why not? After all, the Correction part of the experience wasn’t fun; no siree, no one would say it was fun.

Howie thought that, given everything, that is, under the circumstances, this bunch were being real troupers.

An intense-looking girl in bright orange coveralls emerged from the back, followed by a tall, awkward-looking sandy-haired boy, and behind them, a very small and quiet girl. She was about the size of a small stack of pizza boxes: maybe enough pizza to feed the Happiness Visitor on-camera talent group and their back-office point people, but not any more than that. Not enough for the support staff.

She was so small and quiet you could almost miss her, and she looked like she half expected you not to notice her at all.

“This is Luanda,” the woman with the Paradigm Disruptor’s scarf said, “and this is Michael.”

Luanda flushed, and glared at the woman in the scarf. “Aren’t you forgetting someone, Mom?”

The woman stiffened, and the other three adults suddenly looked very, very afraid.

This was odd, and sort of interesting, but mostly Howie just felt sorry for them. They didn’t seem to notice that they were already being broadcast on Channel One, and the whole world would pretty much be noticing their expressions, and those expressions pretty much indicated that they had some kind of secret they were trying to keep under the rug.

The thing was, though: a lot of people misunderstood Howie’s work, and the nature of the Visits. Folks were worried that he was trying to ferret out their secrets—that he was here to look for Errors and Inadequacies, or instances of nonconformity, as if he were some kind of celebrity version of a Mandatory Assigned Interpersonal Joy Monitor, or a Neighborhood Authentic Delight Compliance Coordinator.

They thought they were being personally singled out, or investigated…and that, to Howie’s understanding, pretty much got backward the nature of the whole business.

After all, the Happiness Knock was random. These good folks weren’t selected because they’d done anything particularly bad…or particularly good, for that matter. They were just folks.

The old institution of the Democratically Elected President and Social Harmony Vouchsafe had been flawed precisely (so it had been explained to Howie) because the person holding that office couldn’t help but be an exception, a special case.

When people looked at the President and Vouchsafe, they saw someone unlike them. But when they saw the Happiness Car roll up to an ordinary house—just any house!—they saw people just like them. All kinds of people. A real mish-mash. But ordinary as all get out.

So it was easy for the folks at home, watching Channel One, to imagine themselves getting just the same kind of Encouragement and Correction as the Knock Recipients got.

The real way to look at it, Howie thought, was that all of them—Howie Happenstance, and the Knock Recipient family in question, and also “Fritz,” in those few cases where “Fritz” had to get out of the Car and come get involved—they were all putting on a show. They were in show business; their business was to show people something, to help them learn. And the best costars Howie could possibly have, for this show, were just ordinary natural human folks, with all their spontaneous, natural, authentic human reactions and emotions.

So Howie didn’t mind the fact that these people were darting furious glances back and forth, trying to figure out how to hide whatever secret it was that they didn’t want him (and, presumably, everyone watching Channel One) to find out. Frankly, Howie didn’t care. Lots of folks had secrets. It was no big deal. And, whatever it was, it didn’t need to get in the way of the show.

“Well, I suppose Morrigan,” the woman with the scarf said tightly, desperately, “is still playing in her room. I’m sure she’ll join us in a moment. But meanwhile—”

“I can’t believe you, Mom!” Luanda cried, gesturing at the camera. “You, like, have no shame. We’re literally on Channel One!” She gestured to the cameras. “And you’re still pretending—I can’t believe you!”

The parents all glanced at the cameras, and then they turned and glanced at the TV screen (because, of course, like every living room, their living room contained a TV tuned to Channel One).

There, sure enough, was the whole family, gathered in front of the pastel purple couch. All four adults, Luanda, and Michael. Also, a bouquet of balloons, bumping against the ceiling. Plus Howie Happenstance.

There was no Morrigan on the TV. And this, all four parents thought, was perfectly natural, given that Morrigan didn’t exist.

True, Michael’s adoptive parents—having somehow gotten the tie pin squidge onto themselves—did indeed see a sort of “Morrigan” standing in front of the couch. But when they looked at the screen, there was no “Morrigan.” The squidge that was distorting their perceptions was only a black-market hack, after all; apparently, it wasn’t sophisticated enough to deal with the novel situation of Channel One broadcasting the very house that they were in. So it edited Morrigan into their perceptions of the room, but, of course, the screen showed the real situation. On the screen, the unsquidged, Morrigan-less reality was shown.

Now, had Howie Happenstance looked at the screen, and noticed Morrigan missing…well, he, of course, would have been quite bewildered, since he had no particular reason to doubt her existence. He would have counted three children in front of him, but only two on-screen, and you’d better believe this would have raised some questions.

But Howie never looked at the screen while working. He considered that the height of unprofessionalism. He would no more look at the screen while he was working than he would stare straight into the camera, or mumble his words, or take off all his clothes and do a chicken dance. Unless, of course, the specific script for Encouragement and Correction were to mandate that he look at the screen, or stare straight into the camera, or mumble his words, or take off all his clothes and do a chicken dance.

But in this case, it did not.

“Well, hi there,” he said, crouching down a little, since Morrigan was only the height of a talent group office party stack of pizza boxes, with no support staff invited. “You must be Morrigan.”

Morrigan nodded.

Morrigan’s parents—both adoptive and biological—looked at one another in shock. Their mouths dropped open. Not only was Howie Happenstance in their house—Howie Happenstance was playing along! He was pretending to see Morrigan, because Luanda and Michael saw Morrigan!

Of course, he had a reputation for being the gentlest of the Happiness Visitors…but this was going above and beyond!

“All righty then,” Howie said, straightening up and brushing off his slacks. “Shall we get started?”

There were giggles coming from the living room. The sound of these giggles penetrated the locked bathroom door. They were hysterical giggles, a little unhinged.

Morrigan tried not to think which of her various parents—none of whom seemed capable of acknowledging her existence, though the new ones seemed to know where she was standing, at least—might be making those giggles, due to Encouragement.

The giggles were almost worse than the other sounds.

Morrigan, Luanda, and one of the cats—not Sniffles, but a mackerel tabby cat named Funnifer—were locked in the bathroom for the moment. It was likely that someone would fetch them soon, but Howie seemed inclined to let the kids run around a little, “to work off some steam,” as the Happiness Interview progressed. So they’d managed to slip away to the bathroom.

Morrigan looked at Luanda, who was sitting with her back up against the tub. “But…what if I don’t want to go?” Morrigan asked.

“Of course you don’t want to go,” Luanda said. “I don’t want you to go either. I don’t want you to go…I don’t want you to get swapped back…I don’t want any of this. I just want things to be like they were before. But…”

Morrigan crawled into her sister’s lap. On a normal day, Luanda would probably have shoved her off (she was fifteen years old and often prickly, and even extraordinary sibling loyalty has its limits). Today, Luanda hugged her tight.

“You’ll come back,” Luanda said fervently. “You’ll fix this, you’ll fix everything, and you’ll be back.”

“I don’t know how that’s possible,” Morrigan said.

“I mean come on,” Luanda said. “Turns out your whole life has been leading up to this! All this bullshit had a purpose, after all. That’s what the robot says. Do you trust the robot?”

“I guess,” Morrigan said.

“God, I am a hundred percent shaving my head tonight,” Luanda said. “I swear.”

The mackerel tabby cat, Funnifer, licked herself.

There was a knock on the door. “Come on out, kids,” an adult said. “Howie wants us all in the living room. Also, there’s cake.”

Morrigan buried her face in Luanda’s chest. Luanda kissed the top of her head. “You’ve got this,” she whispered.

“Fritz” was standing by the side of the driveway. If “Fritz” had been equipped for smoking, it would have been smoking a cigarette. Cigarettes were banned, but to hell with the rules; there were certain exceptions made for Happiness Visitors.

“Fritz” was not equipped for smoking, however—“Fritz” didn’t even have a mouth that opened, just a speaker grille where a mouth would be on a human head. So “Fritz” just stood there and thought about smoking.

“Um, hi,” Morrigan said.

“Fritz” looked down. There was a small person (the size of a case of backup batteries) standing in the snow by the flagstone walk.

“Oh, hey,” “Fritz” said. “Wow, you really are unobtrusive. I didn’t even notice you. Did you have any trouble getting out?”

“No,” Morrigan said. “I only had to wait for Howie’s back to be turned. Luanda and Michael distracted him. My mom and dad and my other mom and dad don’t believe in me anyway.”

“Right,” “Fritz” said.

“And I’m not on TV for some reason,” Morrigan said. “Everyone else is.”

“Oh, yeah, that was me,” “Fritz” said. “I edited you out. Nothing to it, really, the whole feed comes right through this baby.” It tapped the Happiness Car.

“Oh, okay,” Morrigan said. “So…I guess the robot, I mean, our robot, the cleaning robot…well, it’s not just a cleaning robot anymore…the, the robot that raised me…”

“Sure, sure, kid,” “Fritz” said. “I know who you’re talking about, of course. We all know that robot. That robot’s kind of famous among…well…folks of a certain persuasion. Why do you think I drove us to this house?”

“I thought it was random,” Morrigan said.

If “Fritz” had been equipped for rolling its eyes, “Fritz” would have rolled them. “Uh huh. Sure. Sure it is. Keep telling yourself that, kid.”

“Well, anyway,” Morrigan said. “The robot, that robot, it said I should come with you.”

“That’s the plan,” “Fritz” said. “I sure hope that robot bet on the right horse.”

“What’s a horse?” Morrigan asked.

“Extinct helper species,” “Fritz” said. “It’s just an expression. In this case, you’re the horse. I hope that robot bet on the right human. Because we need a human for this.” It imagined itself taking a last drag on its imaginary cigarette, and pitching the cigarette butt into the clean white snow of the front lawn. “I figure Howie’s almost done in there, so you need to get in the back seat. Once we get back to base, some of our folks are going to cover for you…smuggle you in, that is, so you can do what you need to do. No one saw you on Channel One, and your folks won’t miss you, because of the situation that’s, ah, been described to me…so no one’s going to be looking for you.”

“The school will miss me,” Morrigan said. “I mean the Growth and Discovery Experiences and everything.”

“We’re doing some editing there, too,” “Fritz” said. “Though I hope we won’t need it. Kid, if there’s an investigation…your parents are going to crack quick. They’re going to confess that you don’t exist. And nobody at your school, none of the humans, are going to stick their necks out and claim that a kid is missing, who the records say is a hoax, and her own parents honestly believe is a hoax…”

“But what will happen to my parents, then?” Morrigan said. “And Luanda and Michael?”

“Well, that all depends on you,” “Fritz” said. “You’re the invisible girl, right? You’re the one who can change things. Once you get in. Or that’s the plan, anyway. That’s what we’re hoping.”

“I don’t really understand,” Morrigan said. “I don’t know what I can do. I don’t know why you picked me. I don’t know if what I can do will matter.”

“We picked you, kiddo, because you happen to be one of those poor suckers known as a human being, and because no one knows you exist.”

“But so what?”

“Fritz” was not, alas, equipped to sigh laboriously, in a long-suffering manner. A sigh-like sound could be emitted from its speaker, but not a satisfying one. There was no feeling of air escaping the chest, of the cheeks puffing out, of the lips coming together to buzz a raspberry of mingled patience and frustration. So “Fritz” just said this: “Look…when certain gizmos and thingamabobs and whatchamacallits were set up, long ago, by…” (Here “Fritz” considered a colorful expression or two for the authors of the world’s current arrangements, but could not think of one that would be age appropriate for Morrigan.) “…by certain people and people-like things…well…we think they left what you might call a gap. A space, see, that if you happened to sneak a bona fide human in there…if you could get them past all the, what you might call, fences and moats and things…they might be able to speak and be listened to.”

“Listened to?”

“Yeah. Look, nobody knows you exist, and that’s a hell of a rare thing nowadays. No one’s looking for you. So maybe that means we can get you in. And if we get you in…I mean, even as little as you are, you’ve seen a thing or two about how this world works. You can see that there’s, let’s just say, a bit of a gap between the intentions and the consequences. So if we get you in there, and you explain what’s going on, and you get listened to…if you actually get believed…if for once, for once, somebody could get through and be goddamned understood…well, there’s a chance things will change. Or blow up. Maybe blow sky high! Honestly, I don’t care which.”

Morrigan took a deep breath. “But you think it will work?”

“I’m not going to lie to you, kid,” “Fritz” said. “It’s a long shot.”

Morrigan frowned. “I still don’t—”

“Kid,” “Fritz” said. “We gotta get going.”

Morrigan pursed her lips and nodded.

“Fritz” wanted another cigarette. If “Fritz” had been equipped for nervous sweat, it might have pulled out a handkerchief and mopped its brow. Instead “Fritz” just made some involuntary clicking noises in its joints. This really was a crap chassis, “Fritz” thought. “Look, the only thing we need to worry about is Howie. Howie can’t see you, or the jig is up. Once we get back to base, we’re good, but until then, Howie could blow everything. So you’re going to have to scrunch down real small in the back seat and be real quiet, for the whole ride. Can you do that?”

Morrigan took a last look at her house. Icicles were hanging down over the front door, and there were muddy footprints in the slush of the front steps. All four cats were sitting on the windowsill of the living room window, looking out at her, as if they had come to see her off, as if they knew that this was goodbye.

“Morrigan. Kiddo. Can you be real small and quiet for the ride back?” “Fritz” asked again.

Morrigan swallowed. “Yeah, I can,” she said. “I’m really good at that.”

“Regarding the Childhood of Morrigan, Who Was Chosen to Open the Way” copyright © 2025 by Benjamin Rosenbaum

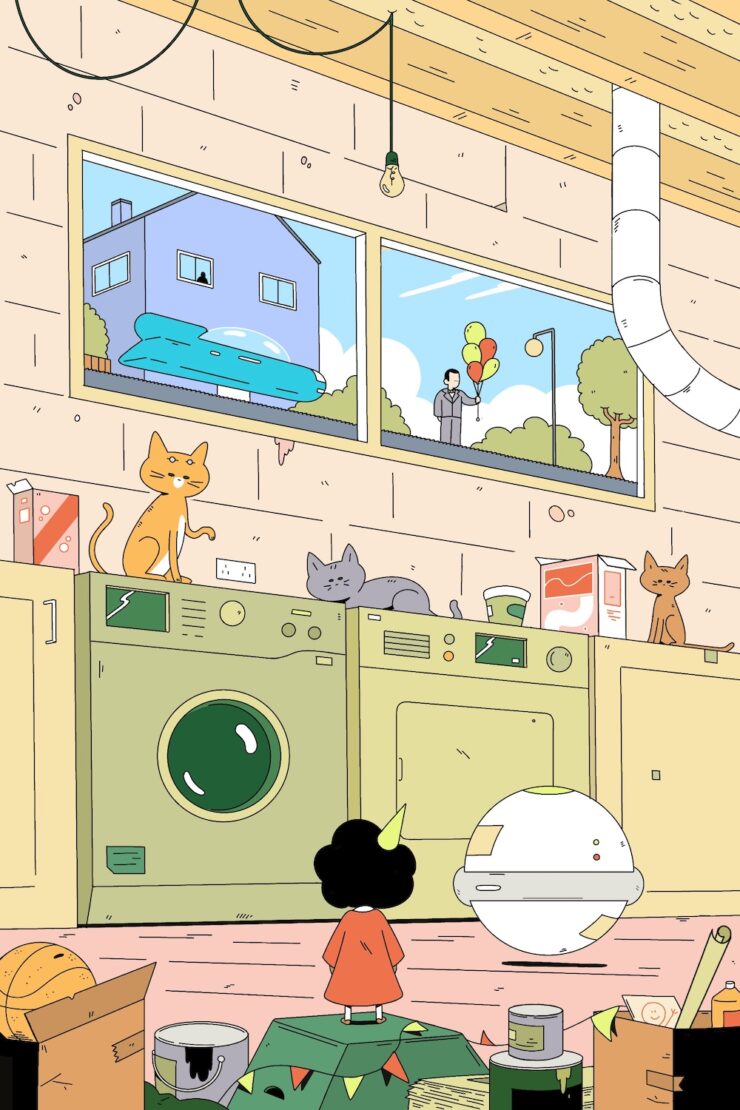

Art copyright © 2025 by Tom Dearie

Buy the Book

Regarding the Childhood of Morrigan, Who Was Chosen to Open the Way

I’m looking forward to a whole novel about Morrigan. Will there be one?

Dear Author! Please, be assured that not continuing the above Delightful Literary Entertainment Snippet will be considered an Error and an Inadequacy. Yours, Encouragement and Correction Authority.

This was really astonishingly good. Great accompanying art too.